-

Posts

3701 -

Joined

-

Last visited

-

Days Won

15

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Events

Blogs

Gallery

Everything posted by MarylandQuitter

-

Tobacco Wars Documentary - Episodes 1, 2 & 3

MarylandQuitter replied to MarylandQuitter's topic in Quit Smoking Discussions

Lilly, I will quit with Wellbutrin XL, another mod quit using NRT so you're in pretty good company. The goal is to get off of nicotine as quickly as possible and for some, that involves the temporary use of NRT. Keep going!! -

NOPE!

-

HA! That's great news!

-

It sounds like the only uncertainty that you have is giving in after some wine. Don't drink the wine. Perhaps tonight the wine can wait because remaining a non-smoker is far more important. No comparison, actually. I hope you went to sleep and will wake up still smoke-free.

-

HA! I think this is the one...

-

Happy Easter!

-

I am really sorry. What a tragic and horrific thing to have to go through. You, the conductor, the family...horrible.

-

March 29, 2019 Stanton A. Glantz, PhD1 The Evidence of Electronic Cigarette Risks Is Catching Up With Public Perception Source Link The advent of electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes), devices that deliver a nicotine aerosol to the lungs by heating a nicotine-containing liquid rather than burning tobacco, has triggered an intense debate over their value for reducing the harm tobacco products cause. The optimists see e-cigarettes delivering nicotine without all the combustion byproducts of conventional cigarettes,1 whereas others point out that e-cigarettes still deliver an aerosol of ultrafine particles and other toxicants that carry substantial health risks.2 A key to realizing the optimists’ vision for e-cigarettes is smokers switching completely from cigarettes to e-cigarettes. Because perceived risks play an important role in selecting tobacco products, Huang and colleagues3 examined how perceptions of the risk of e-cigarettes compared with cigarettes have changed from 2012 to 2017 using 2 national surveys, the Tobacco Products and Risk Perceptions Surveys they conducted and the Health Information National Trends Surveys (HINTS). They found that the fraction of respondents who believed that e-cigarettes were less harmful than cigarettes decreased from approximately 45% in 2012 to approximately 35% in 2017, whereas the fraction who thought they were about the same increased to approximately 45%. (These estimates combine the 2 surveys. The estimates of “about the same” in 2012 were very different in the 2 surveys, so are not listed here; the other results were more similar.) The fractions who thought e-cigarettes were more dangerous than cigarettes increased but remained low, at less than 10%. Huang and colleagues3 express concern that as fewer people view e-cigarettes as less harmful than cigarettes, fewer will be interested in switching from combustible cigarettes to e-cigarettes. Based on the evidence available in 2017, the National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine concluded that “e-cigarettes pose less risk to an individual than combustible tobacco cigarettes.”4(p11) The report emphasized that at the time, no studies on the long-term health effects of e-cigarettes had been performed, which they recognized as a limitation. However, the data are catching up with public perception. Since the report was completed, evidence has started to emerge that e-cigarette users are at increased risk of myocardial infarction,5-7 stroke,6 and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and other respiratory diseases,8-10 controlling for smoking and other demographic and risk factors. Some of these risks approach those of smoking cigarettes. There is also emerging evidence that e-cigarettes deregulate biologically significant genes associated with cancer.11 Equally important, the risks of e-cigarette use are in addition to any risks of cigarette smoking, which means that dual users (people who continue to smoke cigarettes while using e-cigarettes) have higher risks of heart and lung disease than people who just smoke. This finding is particularly important because, contrary to the hopes of the e-cigarette optimists, about two-thirds of adult e-cigarette users are dual users (ie, continue to smoke). In addition, although 1 randomized clinical trial12 has shown that e-cigarettes improve cessation when used as part of a clinically supervised smoking cessation program that includes intensive counseling, as used in the population as a whole as a mass-marketed consumer product, e-cigarettes are associated with reduced odds of cessation.13 In addition, 80% of former cigarette smokers were continuing to use e-cigarettes 6 month later. Although not a direct health effect (in the same way that exposure to e-cigarette aerosol triggers pathophysiological processes that increase the risk of heart and lung disease), this effect of depressing smoking cessation in the population as a whole is another risk of using e-cigarettes. Increased perceived risks of e-cigarettes is also an important element for curbing their use by youth. Youth who believe that e-cigarettes are not harmful or are less harmful than cigarettes are more likely to use e-cigarettes than youth with more negative views of e-cigarettes.14 In terms of overall public health effects, this explosion of youth use swamps any potential harm reduction that may accompany adults switching from cigarettes to e-cigarettes.15 From this perspective, the declining public perception that e-cigarettes are less harmful than cigarettes is a good thing that may turn out to be where the scientific consensus lands as the new evidence on the harms of e-cigarettes continues to accumulate. References 1. Abrams DB, Glasser AM, Pearson JL, Villanti AC, Collins LK, Niaura RS. Harm minimization and tobacco control: reframing societal views of nicotine use to rapidly save lives. Annu Rev Public Health. 2018;39(1):193-213. doi:10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040617-013849PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref 2. Glantz SA, Bareham DW. E-cigarettes: use, effects on smoking, risks, and policy implications. Annu Rev Public Health. 2018;39:215-235. doi:10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040617-013757PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref 3. Huang J, Feng B, Weaver SR, Pechacek TF, Slovic P, Eriksen MP. Changing perceptions of harm of e-cigarette vs cigarette use among adults in 2 US national surveys from 2012 to 2017. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(3):e191047. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.1047ArticleGoogle Scholar 4. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Public Health Consequences of e-Cigarettes. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2018. doi:10.17226/24952 5. Alzahrani T, Pena I, Temesgen N, Glantz SA. Association between electronic cigarette use and myocardial infarction. Am J Prev Med. 2018;55(4):455-461. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2018.05.004PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref 6. Ndunda PM, Muutu TM. Electronic cigarette use is associated with a higher risk of stroke. International Stroke Conference 2019 Oral Abstracts. Stroke. 2019;50(suppl 1):abstract 9. https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/str.50.suppl_1.9. Accessed February 8, 2019. 7. Bhatta D, Glantz SA. Electronic cigarette use and myocardial infarction among adults in the United States Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health. Paper presented at: Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco Annual Meeting; February 20-23, 2019; San Francisco, CA. Abstract P0S4-99. https://cdn.ymaws.com/www.srnt.org/resource/resmgr/SRNT19_Abstracts.pdf. Accessed February 26, 2019. 8. Perez M, Atuegwu N, Mead E, Oncken C, Mortensen E. E-cigarette use is associated with emphysema, chronic bronchitis and COPD (A6245). American Thoracic Society Session D22: Cutting Edge Research in Smoking Cessation and E-cigarettes. http://www.abstractsonline.com/pp8/#!/4499/presentation/19432. Published May 23, 2018. Accessed February 9, 2019. 9. Wills TA, Pagano I, Williams RJ, Tam EK. E-cigarette use and respiratory disorder in an adult sample. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019;194:363-370. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.10.004PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref 10. Bhatta D, Glantz SA. Electronic cigarette use is associated with respiratory disease among adults in the United States Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health: a longitudinal analysis. Paper presented at: Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco Annual Meeting; February 22-23, 2019; San Francisco, CA. Abstract P0S2-146. https://cdn.ymaws.com/www.srnt.org/resource/resmgr/SRNT19_Abstracts.pdf. Accessed February 26, 2019. 11. Tommasi S, Caliri AW, Caceres A, et al. Deregulation of biologically significant genes and associated molecular pathways in the oral epithelium of electronic cigarette users. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(3):738. doi:10.3390/ijms20030738PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref 12. Hajek P, Phillips-Waller A, Przulj D, et al. A randomized trial of e-cigarettes versus nicotine-replacement therapy. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(7):629-637. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1808779PubMedGoogle Scholar 13. Kalkhoran S, Glantz SA. E-cigarettes and smoking cessation in real-world and clinical settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Respir Med. 2016;4(2):116-128. doi:10.1016/S2213-2600(15)00521-4PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref 14. Gorukanti A, Delucchi K, Ling P, Fisher-Travis R, Halpern-Felsher B. Adolescents’ attitudes towards e-cigarette ingredients, safety, addictive properties, social norms, and regulation. Prev Med. 2017;94:65-71. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.10.019PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref 15. Soneji SS, Sung HY, Primack BA, Pierce JP, Sargent JD. Quantifying population-level health benefits and harms of e-cigarette use in the United States. PLoS One. 2018;13(3):e0193328. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0193328PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

-

- 1

-

-

https://whyquit.com/joels-videos/contrary-to-what-you-may-have-heard-vaping-is-not-safe/ Many people are being told and often truly believe that using electronic cigarettes or other vaping products is safe or nearly harmless. This video and its associated resource page explains why so many people believe this statement and how they are wrong. Resources referred to in this video: Professor Simon Chapman’s blog referred to in this video Critical review of Public Health England’s view that vaping is 95% safer than smoking Other related resources: Vaping: What you can’t see can still hurt you STUDENT ALERT: e-cigarettes and juuling are dangerous We ignored the evidence linking cigarettes to cancer. Let's not do that with vaping Premature deaths caused by smoking A conflict of interest is strongly associated with tobacco industry-favourable results, indicating no harm of e-cigarettes. Our views on the need for harm reduction Resources regarding the use of electronic cigarettes as a quitting aid Parent to parent e-cigarette, Juul and nicotine addiction warnings Kids and vaping: an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure

-

- 1

-

-

Abby, so sorry that you're having to deal with this. Being this is caused from an autoimmune disease, are they able to stop any of this? Thanks for the wise words and the great reminder.

-

lol!!! Many could successfully argue that one!

-

You all are far too kind! This forum is what it is because if you all. Playing and simple, just a fact. I changed the logo last night- just straightened a couple lines here and there and also added some smoke. Our Facebook and Twitter pages got a nice refresh as well.

- 22 replies

-

- 12

-

-

-

NOPE!

-

Katie Byrne on vaping: 'In a matter of months, my e-cigarette became more like a child's pacifier' Katie Byrne March 6 2019 2:30 AM https://www.independent.ie/life/health-wellbeing/katie-byrne-on-vaping-in-a-matter-of-months-my-ecigarette-became-more-like-a-childs-pacifier-37881250.html?fbclid=IwAR1id2gXzi1GnMIWBbGkcxqtcV3zejcbCCC8MRG3uUZ3e7uw9ZaqEdTXFO4 It's National No Smoking Day today, but as someone who has a chronic nicotine addiction, I'm not entirely sure if I should be celebrating it. Granted, I don't habitually smoke cigarettes anymore and that's an achievement in anyone's language. But I'm still addicted to nicotine. In fact, I worry that I might be more addicted to it than ever before. Like a lot of smokers, I swapped cigarettes for e-cigarettes a few years ago. Vaping gives ex-smokers the familiar white plumes of smoke (or rather vapor), the satisfying throat hit (don't judge - I'm an addict) and the habitual hand-to-mouth action. In other words, it's pretty easy to make the transition - or at least, as easy as it gets. The trouble is that it's almost too easy. Those who might only have smoked outdoors can now vape indoors; those who once worried about the musty smell of tobacco on their clothes need now only worry about the syrupy scents of cola, vanilla and bubblegum. For someone who is addicted to nicotine, the convenience factor can be the difference between smoking a cigarette every few hours and vaping every few minutes. In a matter of months, my e-cigarette became more like a child's pacifier. Save for the times when it was charging, it was never far from my hands. I vaped while I worked. I vaped while I cooked. I vaped while I vaped. And I wasn't alone. I know dozens of people whose vaping habits have become compulsive; people who thought e-cigarettes could help them wean off nicotine but who actually ended up consuming more of the chemical than ever before. I eventually swapped vaping for nicotine spray after a friend remarked that I needed my e-cigarette like an astronaut needs their oxygen tank. And while it feels good to be free from the finicky paraphernalia of coils and wicks and whatnot, the truth is that I've simply found another long-term nicotine replacement. There is no doubt that vaping and other forms of nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) have helped millions of people to quit smoking but it's important that we see through the smokescreen and recognise that these companies aren't always focused on freeing people from nicotine dependence. Good vape shops, for example, will help new customers to devise a programme that allows them to gradually reduce their nicotine intake and, with it, their vaping habit. The problem, of course, is that the vast majority of these businesses are too busy trying to reposition the vaping habit as a casual "hobby". The global smoking cessation market is expected to reach over $22bn by 2024. When you consider these eye-watering figures, you begin to understand that nicotine products like gums, lozenges, e-cigarettes and so-forth are being used as long-term lifestyle drugs rather than temporary quit aids. Again, it's a much better proposition than being addicted to cancer-causing cigarettes, but it's still a form of addiction and addiction is still a drag (even when it has a fresh minty flavour). On National No Smoking Day, we hear about the thousands of people who successfully quit the habit (80,000 Irish people have given up smoking over the past three years, according to a recent Healthy Ireland survey) but we hear nothing about the people who are still addicted to nicotine-based products. Nor do we hear about the emerging health threat of teenage nicotine addiction The FDA recently described the use of e-cigarettes among young people as an "epidemic". What's interesting is that this generation never smoked cigarettes. What's more, they are addicted to new generation, nicotine salt-based e-cigarettes like Juul, which deliver a smoother and faster throat hit. Ireland aims to be completely tobacco-free by 2025, and while that's a target that we can all get behind, we should be careful not to trivialise the issue of nicotine dependence in the process. More than that, we should understand the true success rates of NRT - that is the numbers of people who successfully quit all nicotine products after using them - before we recommend them to quitters. After years of using nicotine-replacement products, I'm beginning to realise that only good old fashioned cold turkey is going to help me overcome nicotine dependence, just as I'm beginning to wonder if I've been delaying the inevitable all along.

-

E-cigarettes linked to heart attacks, coronary artery disease and depression Data reveal toll of vaping; researchers say switching to e-cigarettes doesn't eliminate health risks Date: March 7, 2019 Source: American College of Cardiology Summary: Concerns about the addictive nature of e-cigarettes -- now used by an estimated 1 out of 20 Americans -- may only be part of the evolving public health story surrounding their use, according to new data. New research shows that adults who report puffing e-cigarettes, or vaping, are significantly more likely to have a heart attack, coronary artery disease and depression compared with those who don't use them or any tobacco products. https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2019/03/190307103111.htm?fbclid=IwAR1NaJHW2AC6fQ8duo1sOIk6Dhh_Ysedp_5_JjtE8k7JlLzxzqXZB289ZLw Concerns about the addictive nature of e-cigarettes -- now used by an estimated 1 out of 20 Americans -- may only be part of the evolving public health story surrounding their use, according to data being presented at the American College of Cardiology's 68th Annual Scientific Session. New research shows that adults who report puffing e-cigarettes, or vaping, are significantly more likely to have a heart attack, coronary artery disease and depression compared with those who don't use them or any tobacco products. "Until now, little has been known about cardiovascular events relative to e-cigarette use. These data are a real wake-up call and should prompt more action and awareness about the dangers of e-cigarettes," said Mohinder Vindhyal, MD, assistant professor at the University of Kansas School of Medicine Wichita and the study's lead author. E-cigarettes -- sometimes called "e-cigs," "vapes," "e-hookahs," "vape pens" or "electronic nicotine delivery systems" -- are battery-operated, handheld devices that mimic the experience of smoking a cigarette. They work by heating the e-liquid, which may contain a combination of nicotine, solvent carriers (glycerol, propylene and/or ethylene glycol) and any number of flavors and other chemicals, to a high enough temperature to create an aerosol, or "vapor," that is inhaled and exhaled. According to Vindhyal, there are now more than 460 brands of e-cigarettes and over 7,700 flavors. E-cigarettes have been gaining in popularity since being introduced in 2007, with sales increasing nearly 14-fold in the last decade, researchers said. But they are also hotly debated -- touted by some as a safer alternative to smoking tobacco, while others are sounding the alarm about the explosion of vaping among teens and young adults. This study found that compared with nonusers, e-cigarette users were 56 percent more likely to have a heart attack and 30 percent more likely to suffer a stroke. Coronary artery disease and circulatory problems, including blood clots, were also much higher among those who vape -- 10 percent and 44 percent higher, respectively. This group was also twice as likely to suffer from depression, anxiety and other emotional problems. Most, but not all, of these associations held true when controlling for other known cardiovascular risk factors, such as age, sex, body mass index, high cholesterol, high blood pressure and smoking. After adjusting for these variables, e-cigarette users were 34 percent more likely to have a heart attack, 25 percent more likely to have coronary artery disease and 55 percent more likely to suffer from depression or anxiety. Stroke, high blood pressure and circulatory problems were no longer statistically different between the two groups. "When the risk of heart attack increases by as much as 55 percent among e-cigarettes users compared to nonsmokers, I wouldn't want any of my patients nor my family members to vape. When we dug deeper, we found that regardless of how frequently someone uses e-cigarettes, daily or just on some days, they are still more likely to have a heart attack or coronary artery disease," Vindhyal said. The study, one of the largest to date looking at the relationship between e-cigarette use and cardiovascular and other health outcomes and among the first to establish an association, included data from a total of 96,467 respondents from the National Health Interview Survey, a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention-fielded survey of Americans, from 2014, 2016 and 2017. The 2015 survey did not include any e-cigarette-related questions. In their analyses, researchers looked at the rates of high blood pressure, heart attack, stroke, coronary artery disease, diabetes and depression/anxiety among those who reported using e-cigarettes (either some days or daily) and nonusers. Those who reported using e-cigarettes were younger than nonusers (33 years of age on average vs. 40.4 years old). Researchers also compared the data for reported tobacco smokers and nonsmokers. Traditional tobacco cigarette smokers had strikingly higher odds of having a heart attack, coronary artery disease and stroke compared with nonsmokers -- a 165, 94 and 78 percent increase, respectively. They were also significantly more likely to have high blood pressure, diabetes, circulatory problems, and depression or anxiety. The researchers also looked at health outcomes by how often someone reported using e-cigarettes, either "daily" or "some days." When compared to non-e-cigarette users, daily e-cigarette users had higher odds of heart attack, coronary artery disease and depression/anxiety, whereas some days users were more likely to have a heart attack and suffer from depression/anxiety, with only a trend toward coronary artery disease. Researchers said this could be due to decreased toxic effects of e-cigarette usage, early dissipation of the toxic effects, or the fact that it has not been studied long enough to show permanent damage to portray cardiovascular disease morbidity. "Cigarette smoking carries a much higher probability of heart attack and stroke than e-cigarettes, but that doesn't mean that vaping is safe," Vindhyal said, adding that some e-cigarettes contain nicotine and release very similar toxic compounds to tobacco smoking. Nicotine can quicken heart rate and raise blood pressure. There are some limitations. For example, the study design doesn't allow researchers to establish causation, but Vindhyal said it does show a clear association between any kind of smoking and negative health outcomes. He added that self-reported data is also subject to recall bias. The researchers were also unable to determine whether these outcomes may have occurred prior to using e-cigarettes. Further longitudinal data is needed. Story Source: Materials provided by American College of Cardiology. Note: Content may be edited for style and length.

-

nope

-

February 27, 2019 Stanton A. Glantz, PhD https://tobacco.ucsf.edu/e-cig-use-among-kids-doubles-england-enthusiasts-still-trying-ignore-it?fbclid=IwAR0-SzVIKc_Un6QLkvaosKHV1mhOtSBKoL0DV5oVk1UMgJ1EwcDybBaN4iM E-cig use among kids doubles in England ; enthusiasts still trying to ignore it After years of arguing that people didn’t need to worry about increasing e-cig use among kids in England, because of the different (from the USA) regulatory environment, e-cig cheerleading Public Health England announced e-cig use among kids doubled in the last 4 years. And that was before Juul invaded. As expected, the Public Health England (a government agency) minimized the effect, as did, ASH England and other e-cig enthusiasts minimized this huge increase on the grounds that few kids were “regular” e-cig users. This argument ignores the fact that the evidence (collected by e-cig enthusiasts!) shows that among kids who use tobacco in England, more than half are initiating nicotine use with e-cigs and any e-cig use predicts future smoking. Indeed, the “gateway” effect in England is about 12, compared to 3-4 in the USA. And even if the kids did not add cigarettes later, bathing developing brains in nicotine is a very bad thing because the neurological changes are permanent. This argument that “experimentation” with cigarettes among kids is not important is something that the tobacco industry has used for a long time to try and minimize youth smoking. Lauren Dutra and I showed that any cigarette smoking among young teens predicts smoking in their 20’s. At least the media is figuring out that this is a problem. Here is some of the coverage: https://www.thesun.co.uk/news/8516445/number-of-under-18s-using-e-cigarettes-doubles-in-four-years-figures-show/ https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2019/02/27/number-children-vaping-doubles-five-years-new-research-shows/ https://www.dailymail.co.uk/health/article-6747813/amp/Number-children-young-people-vaping-DOUBLES-four-years.html?__twitter_impression=true

-

- 3

-

-

-

Relapsing is NOT a Crime !!!!

MarylandQuitter replied to Doreensfree's topic in Quit Smoking Discussions

Relapsing doesn't mean that you can't quit smoking and certainly doesn't mean that you shouldn't quit smoking immediately. If you've relapsed, it's important to understand this addiction and more importantly to treat your smoking as a drug addiction and work at keeping your life free of cigarette smoking and nicotine regardless of the delivery method. Relapsing isn't a crime but smoking is punishable by death. Video discusses the concept of whether a cigarette induced death should be considered a murder, suicide or an accident. "So I failed in quitting smoking, big deal. I'm not going to feel guilty or be hard on myself. I mean, it is only cigarette smoking - it is not like a crime punishable by death." I had to refrain from laughing at this statement. It was seriously quoted to me by a clinic participant who failed to abstain from smoking for even two days. She had the same old excuses of new job, family pressures, too many other changes going on. But to say that cigarette smoking isn't a crime punishable by death - that was news to me. According to the United Nations, tobacco kills 4.9 million users per year. While we know that these people were killed by tobacco, it is hard to classify these deaths. Were they murders, suicides or accidents? When examining the influence of the tobacco industry, one is tempted to call all tobacco related deaths murder. The tobacco industry uses manipulative advertising trying to make smoking appear harmless, sexy, sophisticated, and adult. These tactics help manipulate adults and kids into experimenting with this highly addictive substance. The tobacco industry knows that if they can just get people started, they can hook them on cigarettes and milk them for thousands of dollars over the smokers' lifetimes. The tobacco institute always contradicts the research of all credible medical institutions that have unanimously stated that cigarettes are lethal. The tobacco institute tries to make people believe that all these attacks on cigarettes are lies. If the medical profession was going to mislead the public about cigarettes, it would be by minimizing the dangers, not exaggerating them. The medical profession has a vested interest in people continuing to smoke. After all, the more people smoke, the more work there is in treating serious and deadly diseases. But the medical profession recognizes its professional and moral obligation to help people be healthier. On the other hand, the tobacco industry's only goal is to get people to smoke, no matter what the cost. It could be argued that a smoking death is suicide. While the tobacco industry may dismiss the dangers, any smoker with even average intelligence knows that cigarettes are bad for health but continues to smoke anyway. But I do not believe in classifying most of the smoking deaths as suicidal. Although a smoker knows the risk and still doesn't stop, it is not that he is trying to kill himself. He smokes because he doesn't know how to stop. A smoking related death is more accidental than suicidal. For while the smoker may die today, his death was in great part due to his first puffs twenty or more years ago. When he started smoking the dangers were unknown. Society made smoking acceptable, if not mandatory in certain groups. Not only did he not know the danger, but also he was unaware of the addictive nature of nicotine. So by the time the dangers were known, he was hooked into what he believed was a permanent way of life. Any smoker can quit, but unfortunately many don't know how. Whatever the classification–murder, suicide or accident–the end result is the same. You still have a chance, you are alive, and you know how to quit. Take advantage of this knowledge. Don't become a smoking statistic – NEVER TAKE ANOTHER PUFF! © Joel Spitzer 1983 -

-

Good to see you, Evelyn!

-

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2019/feb/16/we-ignored-the-evidence-linking-cigarettes-to-cancer-lets-not-do-that-with-vaping?fbclid=IwAR0_B3cmPY64L89_gRqsKrSH1ai5-AT7y9q9nOJbOLzOk9pDN6AjokJrBkM We ignored the evidence linking cigarettes to cancer. Let's not do that with vaping Since 2011, e-cigarettes and vaping has increased in teens since 2011, and we still don’t know the long-term health effects Today, it seems so obvious. Cigarettes and tobacco cause lung cancer. It is remarkable however, that this relationship wasn’t always so clearly defined. In fact, during the initial rise in individual cigarette use, the possibility that they contributed to lung cancer was laughable to some, derided by others. Dr Evarts Graham, a pioneer of lung cancer surgery, openly scolded one of his colleagues and former trainees, Dr Alton Oschner, for suggesting in 1939 that smoking cigarettes was a “responsible factor” for the rise in lung cancer he was seeing in his own clinic. Graham reportedly responded to this suggestion by stating, “Yes, there is a parallel between the sale of cigarettes and the incidence of cancer of the lung, but there is also a parallel between the sale of nylon stockings and the incidence of lung cancer.” In other words, social trends may come and go, but their link to the changing incidence of any medical diagnosis is likely only circumstantial. Physicians and the public continued to be skeptical of the relationship between cigarettes and lung cancer as per capita cigarette consumption rose at a staggering rate in the 1930’s and 1940’s. This, of course, led to the tragic rise in lung cancer rates that lagged behind by approximately a 20- to 30-year period. Described in 1912 as among the rarest of all cancers, lung cancer rose from the ashes of cigarettes to become the most common cancer killer of men by 1955 and of women by about 1990. Classic case control studies in 1950 by Richard Doll and A Bradford Hill and ironically by Evarts Graham himself and a medical student, Ernst Wynder, subsequently provided strong evidence linking cigarettes to lung cancer. Graham, after seeing Wynder’s initial figures outlining the clear correlation between cigarette use and lung cancer, is reported to have remarked, “It is possible that I may have to eat humble pie.” This unfortunately didn’t save Graham, himself a heavy smoker, from succumbing to lung cancer in 1957. It would be seven more years until the seminal Surgeon General’s report in 1964 alerted the nation to the risk of cigarettes and definitively declared a causative link between cigarettes and lung cancer. Why should we relive such a story today? Surely in the rapidly moving world of modern science and research and of widespread dissemination of knowledge, such a debacle would never happen and we could easily get ahead of a social trend with any potential for staggering public health consequences. Unfortunately, that is not the case. We are already well behind on the burgeoning epidemic of e-cigarettes and vaping. Recent articles from the New England Journal of Medicine and from Lancet Respiratory Medicine confirmed that vaping, essentially a non-existent habit in 2011, has continued to increase dramatically in teenagers. In 2018, according to survey data, 16% of 10th graders and 21% of 12th graders had vaped nicotine within the past 30 days. In what is perhaps the best indicator that we are not doing enough to address this crisis, those rates had increased 8% and 10% respectively from 2017, rates which, when applied nationally, translated to a staggering 1.3 million new adolescent vapers in just one year. Personally, I have already heard enough when my eighth-grade son explicitly details the vaping habits of some of his classmates along with their distribution network. This increased incidence of vaping in adolescents comes despite a general lack of knowledge about the long-term effects of e-cigarettes and vaping on lung heath and lung cancer. Certainly, some researchers are trying. Recent reports have demonstrated that e-cigarette vapors can have booster effects on carcinogen-bioactivating enzymes and that DNA damage occurs after long term inhalation, both precursor events to cancer. The high temperature reached by e-cigarette solutions can also generate numerous toxic substances which get inhaled directly into the lungs. These substances cause lung inflammation, another well-known precursor to cancer and other lung diseases. E-cigarette vapor may disable protective immune cells in the lung, cells which are vital to the clearance of harmful particles from the lungs and which may have a role in surveillance against precancerous cells. All of these effects are magnified with the addition of nicotine to the vapor. Although many teenagers may vape with just “flavoring”, a high proportion of vaping teens are also using e-cigarettes for the nicotine, which should justifiably raise fears that vaping will become a gateway for long-term addiction and potentially for transition to regular cigarette use. Shockingly, a single JUUL cartridge may contain as much nicotine as a whole pack of regular cigarettes. A real public health concern over the risk of nicotine addiction should therefore be front and center in the e-cigarette debate. Fortunately, policy makers are beginning to rise to the task. Scott Gotlieb, the Food and Drug Administration Commissioner, has begun to target flavoring and marketing practices that appeal to adolescents and has warned that further regulatory restrictions are forthcoming. Such actions should be applauded. As a society, we have to get ahead of this issue. The e-cigarette industry is clearly not going to regulate itself, much like big tobacco before it. E-cigarettes should be treated as medications to aid smoking cessation (where they likely have a real role and potential benefit) and subjected to the same rigorous regulations that govern development, approval, and prescribing practices of other medications. We remain shockingly ignorant about what the combustible liquids within e-cigarettes actually contain. We already made that mistake with tobacco and cigarettes. Without a doubt turning a blind eye and minimizing the risks of tobacco hurt people – our family members, our friends, and our colleagues – and helped to inflict an enormous cancer burden on them and upon our society. There are few things as heartbreaking as seeing the regret and self-blame of a former smoker newly diagnosed with lung cancer long after he or she got wise and gave up their cigarettes. Let’s not repeat those mistakes and regrets with e-cigarettes and vaping. Dr Brendon Stiles is a cardiothoracic surgeon at New York-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell medical center and the chair of the Lung Cancer Research Foundation. Steve Alperin is the CEO of SurvivorNet, a media outlet for cancer information

-

- 2

-

-

Angelica LaVito | @angelicalavito Published 1:00 PM ET Mon, 11 Feb 2019 Updated 6:41 PM ET Mon, 11 Feb 2019 https://www.cnbc.com/2019/02/11/e-cigarettes-single-handedly-drives-spike-in-teen-tobacco-use-cdc.html?fbclid=IwAR2jGMZMFU7UOD6rQeDWlcAsOjD_Xt38fifTrTrwEGlbuBTxCcu8-MtSFNI CDC blames spike in teen tobacco use on vaping, popularity of Juul Over the course of a year, the number of high school students using tobacco products increased by about 38 percent, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found. E-cigarettes drove the increase, the CDC said. Use of other products remained stable. In 2018, nearly 21 percent of high school students, or 3 million, vaped. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is blaming nicotine vaping devices like Juul for single-handedly driving a spike in tobacco use among teens, threatening to erase years of progress curbing youth use. Over the course of a year, the number of high school students using tobacco products, which include e-cigarettes, increased by about 38 percent, the CDC found in its annual National Youth Tobacco Survey released Monday. That translates to about 27 percent of high school teens using tobacco products in 2018, the CDC said. Of all the tobacco products the CDC surveys students about, including cigarettes and hookah, only e-cigarettes saw a meaningful increase in use. Among high school students, e-cigarette use surged nearly 78 percent. In 2018, nearly 21 percent of high school students vaped, up from close to 12 percent in 2017. In 2018, 1.5 million more middle school and high school students vaped than in 2017, up to 3.6 million from 2.1 million, according to the survey. While the survey did not specifically ask teens about Juul, Brian King, deputy director for research translation in the CDC's Office on Smoking and Health, said the increase in e-cigarette use coincides with the rise in sales of Juul's products. Teens are also vaping more frequently than before. About 28 percent of teens who are vaping are doing it 20 or more times per month, a 39 percent increase from the 20 percent of teens who were defined as frequent users in 2017, the CDC said. About 40 percent of high school students who said they used tobacco said they used two or more types of products, a 23 percent increase. About 15 percent of them vaped and smoked cigarettes, according to the survey. The data confirms anecdotal reports that more and more teens have started to use e-cigarettes, particularly Juul. Public health officials, including the CDC, the Food and Drug Administration and the surgeon general, have warned that the trend could reverse two decades of driving down teen smoking rates. "The skyrocketing growth of young people's e-cigarette use over the past year threatens to erase progress made in reducing youth tobacco use," CDC Director Robert Redfield said in a statement. "It's putting a new generation at risk for nicotine addiction." Among other tobacco products, including cigarettes and cigars, the CDC did not find any significant change. That means e-cigarettes were the sole driver of the increase in overall tobacco use, the agency said. E-cigarettes surpassed cigarettes to become the most commonly used form of tobacco among middle school and high school students in 2014. More high school students vape than smoke cigarettes The rate of high school students using e-cigarettes eclipsed the rate of those smoking cigarettes in 2014, according to the CDC's National Youth Tobacco Survey Cigarette smoking among high school students ticked up to 8.1 percent from 7.6 percent. It's not a statistically significant rise, but it still has some concerned. "These survey results are deeply troubling," Matthew Myers, president of the Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids, said in a statement. "They add to mounting concerns that the rise in youth use of e-cigarettes, especially Juul, is vastly expanding the number of kids addicted to nicotine, could be leading kids to and not away from cigarettes, and directly threatens the decades-long progress our nation has made in reducing youth smoking and other tobacco use." The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is blaming nicotine vaping devices like Juul for single-handedly driving a spike in tobacco use among teens, threatening to erase years of progress curbing youth use. Over the course of a year, the number of high school students using tobacco products, which include e-cigarettes, increased by about 38 percent, the CDC found in its annual National Youth Tobacco Survey released Monday. That translates to about 27 percent of high school teens using tobacco products in 2018, the CDC said. JUUL institutes enhanced age verification for online sales 3:02 PM ET Tue, 13 Nov 2018 | 01:56 Of all the tobacco products the CDC surveys students about, including cigarettes and hookah, only e-cigarettes saw a meaningful increase in use. Among high school students, e-cigarette use surged nearly 78 percent. In 2018, nearly 21 percent of high school students vaped, up from close to 12 percent in 2017. In 2018, 1.5 million more middle school and high school students vaped than in 2017, up to 3.6 million from 2.1 million, according to the survey. While the survey did not specifically ask teens about Juul, Brian King, deputy director for research translation in the CDC's Office on Smoking and Health, said the increase in e-cigarette use coincides with the rise in sales of Juul's products. Teens are also vaping more frequently than before. About 28 percent of teens who are vaping are doing it 20 or more times per month, a 39 percent increase from the 20 percent of teens who were defined as frequent users in 2017, the CDC said. About 40 percent of high school students who said they used tobacco said they used two or more types of products, a 23 percent increase. About 15 percent of them vaped and smoked cigarettes, according to the survey. The data confirms anecdotal reports that more and more teens have started to use e-cigarettes, particularly Juul. Public health officials, including the CDC, the Food and Drug Administration and the surgeon general, have warned that the trend could reverse two decades of driving down teen smoking rates. "The skyrocketing growth of young people's e-cigarette use over the past year threatens to erase progress made in reducing youth tobacco use," CDC Director Robert Redfield said in a statement. "It's putting a new generation at risk for nicotine addiction." Among other tobacco products, including cigarettes and cigars, the CDC did not find any significant change. That means e-cigarettes were the sole driver of the increase in overall tobacco use, the agency said. E-cigarettes surpassed cigarettes to become the most commonly used form of tobacco among middle school and high school students in 2014. Cigarette smoking among high school students ticked up to 8.1 percent from 7.6 percent. It's not a statistically significant rise, but it still has some concerned. "These survey results are deeply troubling," Matthew Myers, president of the Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids, said in a statement. "They add to mounting concerns that the rise in youth use of e-cigarettes, especially Juul, is vastly expanding the number of kids addicted to nicotine, could be leading kids to and not away from cigarettes, and directly threatens the decades-long progress our nation has made in reducing youth smoking and other tobacco use." Surgeon General Jerome Adams has declared youth e-cigarette use an epidemic. The FDA is trying to limit illegal sales to minors. The agency is drafting new rules that would limit flavored nicotine pods to age-restricted stores like vape shops. The agency plans to publish the proposed regulation within the next month, Commissioner Scott Gottlieb told CNBC last week. Gottlieb said Monday that the FDA is also exploring possible civil and criminal enforcement tools "to target potentially violative sales and marketing practices by manufacturers as well as retailers." "These trends require forceful and sometimes unprecedented action among regulators, public health officials, manufacturers, retailers and others to address this troubling problem," Gottlieb said in a statement. Juul spokeswoman Victoria Davis said the company is "committed to fighting underage use of vaping products, including Juul products."

-

- 2

-

-

-

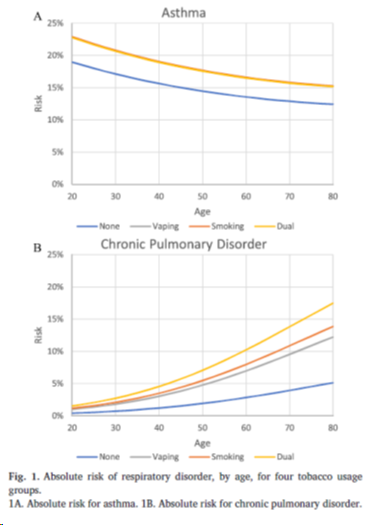

February 7, 2019 Stanton A. Glantz, PhD https://tobacco.ucsf.edu/new-evidence-e-cigs-pose-substantial-risks-adult-asthma-and-copd-similar-cigarettes?fbclid=IwAR2JN2Zs7JirmTnSfAJLHsO-1xb13bt_fV8IxIJT8PyyEQReJN3s_GpUFmM New evidence that e-cigs pose substantial risks of adult asthma and COPD similar to cigarettes Tom Wills and colleagues just published “E-cigarette use and respiratory disorder in an adult sample,” documenting the link between e-cigarette use and asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, controlling for smoking among a large sample of Hawaiians. The found e-cigs increase the risk of COPD by a factor of 2.58, with dual users (people use e-cigarettes and cigarettes at the same time) higher than using cigarettes or e-cigarettes alone. They found similar risks for e-cigarettes, cigarettes, and dual use for asthma. This figure, from their paper, makes these points nicely. Note that the lines for e-cigarettes, cigarettes, and dual use all fall on top of each other, above the line for nonsmokers. For COPD, the risks of e-cigarettes and cigarettes are similar, with dual use above both of them. The COPD results for dual use are particularly important since about 70% of e-cigarette users continue to smoke (i.e., are dual users). It adds to the case that, in terms of respiratory disease, e-cigarettes are about as bad as cigarettes, but also are different from cigarettes and add to the risk of smoking. (This is the same finding we found for heart attacks.) These results are consistent with an earlier study using PATH showing that e-cigarette users were at higher risk of COPD, controlling for smoking. Here is the abstract: OBJECTIVES: Little evidence is available on the association of e-cigarettes with health indices. We investigated the association of e-cigarette use with diagnosed respiratory disorder among adults in data from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance Survey (BRFSS). METHODS: The 2016 Hawaii BRFSS, a cross-sectional random-dial telephone survey, had 8087 participants; mean age was 55 years. Items asked about e-cigarette use, cigarette smoking, and being diagnosed by a health professional with (a) asthma or (b) chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Multivariable analyses tested associations of e-cigarette use with the respiratory variables controlling for smoking and for demographic, physical, and psychosocial variables. RESULTS: Controlling for the covariates and smoking there was a significant association of e-cigarette use with chronic pulmonary disorder in the total sample (AOR = 2.58, CI 1.36-4.89, p < 0.01) and a significant association with asthma among nonsmokers (AOR = 1.33, CI 1.00-1.77, p < 0.05). The associations were stronger among nonsmokers than among smokers. Results were similar for analyses based on relative risk and absolute risk. There was also a greater likelihood of respiratory disorder for smokers, females, and persons with overweight, financial stress, and secondhand smoke exposure. CONCLUSIONS: This is the first study to show a significant independent association of e-cigarette use with chronic respiratory disorder. Several aspects of the data are inconsistent with the possibility that e-cigarettes were being used for smoking cessation by persons with existing respiratory disorder. Theoretical mechanisms that might link e-cigarettes use and respiratory symptoms are discussed. The full citation is: Wills TA, Pagano I, Williams RJ, Tam EK. E-cigarette use and respiratory disorder in an adult sample. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019 Jan 1;194:363-370. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.10.004. Epub 2018 Nov 7. It is available here.

-

The importance of the first three days of your quit

MarylandQuitter posted a blog entry in MarylandQuitter's Blog

Video highlights the fact that while the intensity and exact duration of physical withdrawals can vary widely when first quitting smoking, that any peak symptoms will ease up once the person gets through the first three days.