-

Posts

3680 -

Joined

-

Last visited

-

Days Won

15

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Calendar

Blogs

Gallery

Posts posted by MarylandQuitter

-

-

-

Preventing Tobacco Use Among Youth and Young Adults

-

Fact Sheet

This is the 31st tobacco-related Surgeon General’s report issued since 1964. It describes the epidemic of tobacco use among youth ages 12 through 17 and young adults ages 18 through 25, including the epidemiology, causes, and health effects of this tobacco use and interventions proven to prevent it. Scientific evidence contained in this report supports the following facts:

We have made progress in reducing tobacco use among youth; however, far too many young people are still using tobacco. Today, more than 600,000 middle school students and 3 million high school students smoke cigarettes. Rates of decline for cigarette smoking have slowed in the last decade and rates of decline for smokeless tobacco use have stalled completely.

- Every day, more than 1,200 people in this country die due to smoking. For each of those deaths, at least two youth or young adults become regular smokers each day. Almost 90% of those replacement smokers smoke their first cigarette by age 18.

- There could be 3 million fewer young smokers today if success in reducing youth tobacco use that was made between 1997 and 2003 had been sustained.

- Rates of smokeless tobacco use are no longer declining, and they appear to be increasing among some groups.

- Cigars, especially cigarette-sized cigars, are popular with youth. One out of five high school males smokes cigars, and cigar use appears to be increasing among other groups.

- Use of multiple tobacco products—including cigarettes, cigars, and smokeless tobacco—is common among young people.

- Prevention efforts must focus on young adults ages 18 through 25, too. Almost no one starts smoking after age 25. Nearly 9 out of 10 smokers started smoking by age 18, and 99% started by age 26. Progression from occasional to daily smoking almost always occurs by age 26.

Tobacco use by youth and young adults causes both immediate and long-term damage. One of the most serious health effects is nicotine addiction, which prolongs tobacco use and can lead to severe health consequences. The younger youth are when they start using tobacco, the more likely they’ll be addicted.

- Early cardiovascular damage is seen in most young smokers; those most sensitive die very young.

- Smoking reduces lung function and retards lung growth. Teens who smoke are not only short of breath today, they may end up as adults with lungs that will never grow to full capacity. Such damage is permanent and increases the risk of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

- Youth are sensitive to nicotine and can feel dependent earlier than adults. Because of nicotine addiction, about three out of four teen smokers end up smoking into adulthood, even if they intend to quit after a few years.

- Among youth who persist in smoking, a third will die prematurely from smoking.

Youth are vulnerable to social and environmental influences to use tobacco; messages and images that make tobacco use appealing to them are everywhere.

- Young people want to fit in with their peers. Images in tobacco marketing make tobacco use look appealing to this age group.

- Youth and young adults see smoking in their social circles, movies they watch, video games they play, websites they visit, and many communities where they live. Smoking is often portrayed as a social norm, and young people exposed to these images are more likely to smoke.

- Youth identify with peers they see as social leaders and may imitate their behavior; those whose friends or siblings smoke are more likely to smoke.

- Youth who are exposed to images of smoking in movies are more likely to smoke. Those who get the most exposure to onscreen smoking are about twice as likely to begin smoking as those who get the least exposure. Images of smoking in movies have declined over the past decade; however, in 2010 nearly a third of top-grossing movies produced for children—those with ratings of G, PG, or PG-13— contained images of smoking.

Tobacco companies spend more than a million dollars an hour in this country alone to market their products. This report concludes that tobacco product advertising and promotions still entice far too many young people to start using tobacco.

- The tobacco industry has stated that its marketing only promotes brand choices among adult smokers. Regardless of intent, this marketing encourages underage youth to smoke. Nearly 9 out of 10 smokers start smoking by age 18, and more than 80% of underage smokers choose brands from among the top three most heavily advertised.

- The more young people are exposed to cigarette advertising and promotional activities, the more likely they are to smoke.

- The report finds that extensive use of price-reducing promotions has led to higher rates of tobacco use among young people than would have occurred in the absence of these promotions.

- Many tobacco products on the market appeal to youth. Some cigarette-sized cigars contain candy and fruit flavoring, such as strawberry and grape.

- Many of the newest smokeless tobacco products do not require users to spit, and others dissolve like mints; these products include snus—a spitless, dry snuff packaged in a small teabag-like sachet—and dissolvable strips and lozenges. Young people find these products appealing in part because they can be used without detection at school or other places where smoking is banned. However, these products cause and sustain nicotine addiction, and most youth who use them also smoke cigarettes.

- Through the use of advertising and promotional activities, packaging, and product design, the tobacco industry encourages the myth that smoking makes you thin. This message is especially appealing to young girls. It is not true—teen smokers are not thinner than nonsmokers.

Comprehensive, sustained, multi-component programs can cut youth tobacco use in half in 6 years.

- Prevention is critical. Successful multi-component programs prevent young people from starting to use tobacco in the first place and more than pay for themselves in lives and health care dollars saved.

- Strategies that comprise successful comprehensive tobacco control programs include mass media campaigns, higher tobacco prices, smoke-free laws and policies, evidence-based school programs, and sustained community-wide efforts.

- Comprehensive tobacco control programs are most effective when funding for them is sustained at levels recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

-

Posted at 2:49 pm by David Halperin of Public Report

Posted at 2:49 pm by David Halperin of Public Report

It’s become increasingly clear from law enforcement, congressional, and media investigations that many for-profit colleges are selling a product that can be toxic to students — high-priced, low-quality programs that often leave graduates and dropouts alike without improved career prospects and paralyzed by student loan debt, often $100,000 or more. So when the for-profit college companies’ trade association, APSCU, meets in Washington next week for its annual lobby day, whom has the group selected to speak to its members on the subject of “Crafting the Positive Impact Proposition of Private Sector Colleges and Universities”?

None other than John Dunham, president of John Dunham & Associates, which, according to the firm’s website, guerrillaeconomics.com, is “an economic research firm uniquely focused on government relations.” Dunham ”specializes in the economics of how public policy issues affect products and services.”

Where did John Dunham learn these skills? “Prior to starting his own firm, John was the senior U.S. economist with Philip Morris, producing research and information on key issues facing all of the company’s divisions.” Philip Morris, of course, has long been one of the nation’s largest manufacturers of cigarettes. For decades, the company concealed important truths about the toxic effects of cigarette smoking.

Dunham worked at Philip Morris from 1995-2000, where, among other things, according to his CV, he “performed financial analysis of corporate legal settlements, including the largest in U.S. history.” It was during this period that public perceptions swung decisively against the image of the tobacco companies, and in 1999 the U.S. Justice Department sued Philip Morris and other big tobacco companies for fraud, charging the industry had engaged in a long conspiracy to mislead the public about the dangers of smoking. There are thousands of documents referencing Dunham in the publicly-available archive of tobacco industry materials. (After Dunham left Philip Morris, the government prevailed in the case, and the tobacco companies were ordered to start telling the truth about their harmful products.)

Now, it’s the for-profit colleges that are on the ropes, with mounting federal and state investigations about alleged deceptions and abuses of students and taxpayers, including, this week’s announcement by Consumer Financial Protection Bureau head Richard Cordray that his agency has sued for-profit giant ITT Educational Services and is carefully probing other companies. APSCU is worried, as it should be. According to a report by Wells Fargo market analyst Trace Urdan, APSCU lobbyists met with some state attorneys general and governors’ staff at this week’s National Governors Association meeting in Washington, and “APSCU requested that prior to taking action, the attorneys general provide some notice to the schools’ stakeholders. APSCU reported that some, though not all of the AGs seemed receptive to this notion.”

The industry also faces the challenge of a revised “gainful employment” rule from the Obama Administration, a measure that would eventually cut off federal aid to programs that consistently leave students with overwhelming debt. The CEOs of many of the biggest for-profit colleges have been meeting at the White House to argue against issuance of the rule. The Wells Fargo report says, not surprisingly, that the “theme” of next week’s APSCU meetings with Members of Congress and their staffs “will be stopping the new Gainful Employment regulation.”

APSCU includes ITT, EDMC, Kaplan, Corinthian, Bridgepoint, DeVry, Globe and other companies now accused of fraud and deception, and it has harbored egregious abusers like FastTrain College and ATI up until they’ve been shut down by authorities for systematic fraud.

APSCU and other for-profit college companies have managed to “persuade” many Republicans, and some Democrats, on the Hill through ongoing campaign contributions. But in their lobby meetings, they at least have to appear to argue in terms of the merits. In seeking to sell APSCU’s toxic product on Capitol Hill, and persuading Washington that the industry should continue receiving more than $30 billion a year in taxpayer money, it seems that a veteran of crafting policy arguments for the tobacco industry is the man for the job.

It’s one more sign of the deep cynicism of the big for-profit college companies — and the deep trouble the industry is now in.

Instead of trying again to put lipstick on their diseased pig, wise players in the sector should start figuring out how to change their business model and make money by actually helping students to train, at affordable prices, for genuine careers.

By the way, APSCU has prepared these tips for its members coming to take Washington by storm:

Bring plenty of business cards

Wear comfortable shoes

Carry a bottle of water and small snacks with you (banana, granola bar, trail mix)

Tour Washington, D.C.’s many historical sites (schedule permitting)This article originally appeared on Republic Report

-

Posted at 4:00 pm by Zaid Jilani of Report Public

Why is appearing at Big Tobacco-sponsored conference a greater offense in Australia and New Zealand than in the United States?

Posted at 4:00 pm by Zaid Jilani of Report Public

Why is appearing at Big Tobacco-sponsored conference a greater offense in Australia and New Zealand than in the United States?Last week, Republic Report noted that six governors from both political parties attended a secretive trade talks conference in Washington, D.C. sponsored by a number of multi-national corporations, including Philip Morris International. These governors apparently were comfortable with allowing themselves to be wined and dined by some of the world’s most powerful corporate entities while pushing for a new NAFTA-style trade agreement for the Pacific region.

While U.S. politicians have grown accustom to this sort of stealth corporate lobbying, it appears that some of our overseas neighbors have not. The Australian embassy actually withdrew the Australian ambassador from the conference after it became apparent that Philip Morris would be sponsoring it.

Meanwhile, in New Zealand, several political parties have called for Mike Moore, the country’s ambassador to the United States, to be fired because he attended an event sponsored by the tobacco industry. Other political parties have called for full disclosure of the details of how Moore ended up at the conference, including a disclosure of whether or not he was authorized by the government. Meanwhile, the Public Health Association there roundly condemned Moore.

Cabinet ministers in New Zealand’s federal government have pushed back against calls to censure or withdraw Moore, but it is interesting that his appearance at the conference has become a scandal at all. The reactions by the body politic in New Zealand and Australia to a conference sponsored by Big Tobacco as compared to the nonexistent response in the United States is instructive in how deeply corporate influence in our politics has become a normal affair.

This article originally appeared on Republic Report

-

Posted at 11:00 am by Zaid Jilani of Republic Report

At one point, Taylor pointed out many of Byrd’s various clients, including the tobacco and alcohol industries. Byrd explained that he decided a long time ago that he would work for the “people who pay” and that he wouldn’t be where he is today if he wasn’t able to pass through the Revolving Door as a former lawmaker (he was a Majority Whip):

- TAYLOR: You don’t shy away from controversy. You represented the gaming industry, the tobacco industry, the, some of the alcoholic beverage industry.

- BYRD: If it’s a good idea, motherhood, or Apple Pie, I’m probably opposed!

- TAYLOR: (laughs) There’s social reformers and religious folks who probably think you’re evil for doing that. How do you respond to that?

- BYRD: When I first decided to do this years ago, one of the things I did is I realized that, you know, you’ve gotta go, if you’re going to do this, you have to go where the people are who are going to pay you. [...] There’s a lot of other ways to say it, but that’s being real upfront about it.

- TAYLOR: How do you stay so active in Democratic politics and still get along, you know, successfully with Republicans in Dover?

- BYRD: You know, I’ve always said everything I am in this business and all of my success is a result of me getting elected to the legislature as a Democrat in 1974.

This article originally appeared on Republic Report

-

Published February 24, 2014

Published February 24, 2014

This January marked the 50th anniversary of the first Surgeon’s General report on Smoking and Health. On that anniversary, a new Surgeon General’s report, The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress, was released. Read the report here> That report indicates that since the first report in 1964, more than 20 million premature deaths in the U.S. can be attributed to cigarette smoking.

The report focuses on a myriad of tobacco issues, but one topic keeps recurring: marketing. Thousands of tobacco-related deaths can be tied to marketing by tobacco companies.

For example, the report concludes, “The tobacco epidemic was initiated and has been sustained by the aggressive strategies of the tobacco industry, which has deliberately misled the public on the risks of smoking cigarettes.”

In the 50 years since the first Surgeon General’s report came out, a lot has changed. However, tobacco companies are still marketing cigarettes and cigarettes are still killing over 440,000 Americans each year.

What else can be done?

Maybe the answer lies in criminal liability for these marketing schemes, an idea that is not without precedent. In Williams v. Philip Morris, the Oregon Supreme Court described the tobacco industry’s history of marketing and promotional schemes as “extraordinarily reprehensible,” emphasizing the criminal implications of the harms caused by this industry’s actions. Read the case here>

Additionally, the Oregon Supreme Court discussed the “the possibility of severe criminal sanctions, both for the individual who participated and for the corporation generally,” as a result of aggressive and deceptive promotion of dangerous tobacco products. Perhaps if Big Tobacco is subject to criminal liability for their marketing, we will have a smoke-free society by 2064 – the 100th anniversary of the Surgeon General’s report.

Could criminal liability be the way to end Big Tobacco cigarette marketing?

This article originally appeared on Republic Report

-

Published September 11, 2013

Global trade negotiations in Washington this week will determine how cigarette companies will be able to market their products in developing nations—and potentially, overturn smoking restrictions around the world.

As cigarette smoking has fallen in the United States and Europe thanks to public health laws and liability lawsuits, global tobacco companies have increasingly turned to developing markets to expand their business. Now they’re trying to make sure the largest trade agreement since the World Trade Organization gives them the tools they need to stop those countries from adopting the laws that cost them customers in wealthier nations.“It is very important for people to understand that the industry is using trade law as a new weapon, and [the Trans-Pacific Partnership] provides an opportunity to put a stop to that,” Susan Liss, the executive director of the Campaign for Tobacco Free Kids, says.Like everyone else, cigarette companies turn to emerging marketsSmoking rates are plunging in the US—from 25% of the population in 1990 to 19% today—and similar drops are happening in the United Kingdom, Australia and Canada. Today, of the world’s growing population of 1.3 billion smokers, 80% reside in low or middle-income economies. Tobacco companies naturally want to make sure they can protect and expand their businesses in those markets, especially among women, who have much lower smoking rates than women in wealthier countries.

Until the late 1990s, the US government was keen to help American tobacco companies accomplish this end, threatening trade fights with Japan, Thailand, Taiwan and South Korea unless they opened their borders to US cigarettes and their sophisticated marketing campaigns. A government study found that in the year after US companies entered South Korean markets, smoking among teenagers surged, especially among young women, where the share of smokers increased from 1.6% to 8.7% in just one year.Public health and development organizations decry the expansion of smoking in these countries, fearful not just about the death rate—the World Health Organization estimates that one billion people will die from smoking this century—but also the secondary costs. Those include money spent by the malnourished and poor on cigarettes rather than staples, agricultural labor diverted to inefficient tobacco farming rather than food or other enterprise, and the costs of health care for the myriad ailments associated with cigarette smoking and second-hand smoke. The face of these fears is a chain-smoking Indonesian toddler: -

Published May 16, 2013

Published May 16, 2013

Chris Bostic Deputy Director for Policy

I wonder if Philip Morris International (PMI) researchers have studied the ‘length of public memory.’ If so, the resulting answer seems to be ‘about 15 years.’ That’s how long it has been since the Tobacco Institute closed its doors, after 40 years of obfuscating the science on tobacco addiction, disease and death. A key aspect of industry strategy to forestall meaningful regulation has always been to question the causal link between tobacco and disease.

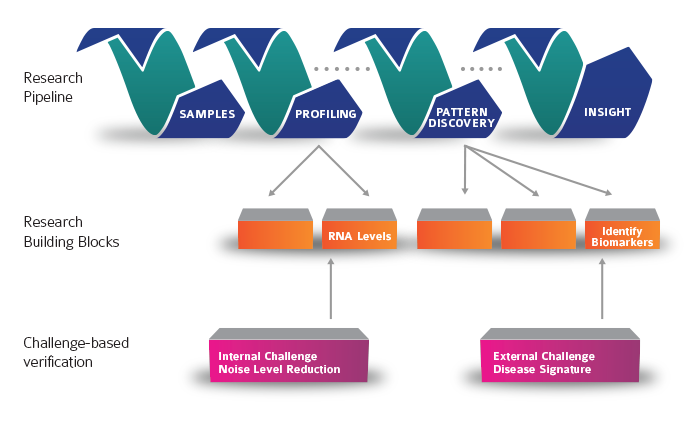

PMI has just launched phase two of its sbv IMPROVER project (the title is short for “systems biology verification of industrial methodology for process verification in research”). The theme is “species translation challenge,” and PMI, in collaboration with technoogy giant IBM, will award three US$20,000 grants to scientists who can best poke holes in translating disease lab results in rodents to humans. In one online article very sympathetic to Philip Morris, the reporter states “not every smoker suffers all or any of those health effects, suggesting that a combination of environmental and genetic factors lead to disease.” This years project follows on the “diagnostic signature challenge,” in 2012 which gave a US$50,000 award for showing genetic markers for diseases linked to tobacco.

The main purpose of IMPROVER seems clear – remuddy the waters on the causal link between tobacco and disease. But they actually get much more. By enticing young researchers to compete, PMI pushes back against the trend among major universities to not do business with big tobacco. These researchers are also a natural recruitment pool for the next generation of scientists who are untroubled by the ethics of working with big tobacco. By linking with IBM, working with universities, and comparing the effort to legitimate scientific endeavors such as DREAM, PMI gains legitimacy among the scientific community.

Finally, IMPROVER is a rather brilliant example of corporate social responsibility marketing. Turning the purpose of the scheme on its head, PMI says its “number one objective is to do something about our dangerous products.” How can anyone argue with that? That’s not rhetorical – I invite responses on all the ways we can argue with that.

On a side note, is the name IMPROVER a subtle nod and affront to MPOWER?

This article originally appeared on Republic Report

-

By Adrienne Jane Burke | April 30, 2013, 1:04 PM | Techonomy Exclusive

It might be surprising to hear a tobacco giant described as a tech innovator. But Philip Morris researchers are pioneering new territory with a crowdsourced approach to checking the accuracy of life sciences data.

In partnership with computational biologists at IBM’s Watson Research Center, Philip Morris’s so-called sbv IMPROVER project creates open challenges to encourage scientists to augment traditional peer reviews of research data. On Monday, Philip Morris launched its Species Translation Challenge, which will award three $20,000 prizes to teams whose results best define how well rodent tests can predict human outcomes.

Similar competitions have emerged in the academic world, but sbv IMPROVER (short for “systems biology verification of industrial methodology for process verification in research” in case you were wondering) is the first that taps the crowd to verify industrial research. An initial challenge last year awarded $50,000 to two Wayne State University researchers who proved best at confirming genetic features that could be considered “diagnostic signatures” for particular diseases.

Why is a cigarette manufacturer sponsoring such competitions? “Our number one objective is to do something about our dangerous products,” says Philip Morris scientific communications director, Hugh Browne. (The company is known for its periodic candor about such matters, even as it continues to dominate the industry.) From heart disease to cancer to emphysema, the potential consequences of smoking are well known. But not every smoker suffers all or any of those health effects, suggesting that a combination of environmental and genetic factors lead to disease.

To understand precisely how smoking and chewing tobacco leads to complex interactions in a user’s biological systems, “Philip Morris is increasing its investments into systems biology,” Browne says. The company is looking at networks of genes, proteins, and biochemical reactions to identify the exact biological mechanisms perturbed by smoking.

But such biological data is notoriously complex to analyze. The profession as yet lacks any standard methodology for verifying results, and traditional peer-review methods have “struggled with the volume and complexity of the data,” according to Philip Morris.

IMPROVER breaks research workflows into components and asks the crowd to apply its own computational methods to verify results. IBM computational biologist Gustavo Stolovitsky says the project “provides an excellent platform on which to test and develop some of the most cutting-edge approaches to the analysis of high-throughput biological data.”

The 2012 IMPROVER challenge asked participants to identify signs in a patient’s set of transcribed genetic material that could be relied on to diagnose any of four diseases associated with smoking: psoriasis, multiple sclerosis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and lung cancer. Competitors looked at clinical data from patients—some of it licensed from third parties and provided by Philip Morris; some from the public domain.

More than 50 teams worldwide competed in the challenge that the Wayne State researchers won. Says Ajay Royyuru, director of IBM’s Computational Biology Center in Yorktown Heights, NY: “There was a refreshing variety of competitors.” The most successful applied fundamental understanding of biology “rather than brute force machine learning,” or automated big-data analysis methods. “Some came at it from a mathematical modeling approach, others came from biology, and others combined those,” he continues. (The Wayne State team comprised a bioinformaticist and a perinatal researcher.) Royyuru adds that the challenges can provide young scientists without scientific publications under their belt with a way to get recognition, and computational biology startup companies with a way to showcase what they can do.

A team of IBM computational biology experts scored entries, and a five-man outside panel reviewed the scores. While no single team identified the data perfectly, the leading methods, considered in the aggregate, performed exceptionally well, Royyuru says.

The new challenge launched this Monday seeks to determine if gene expression pathways identified in rodents will predict the same in humans. Scientists typically rely on them to study the impact of products on consumers, even though it remains unclear how well rodent results translate to humans.

Four sub-challenges ask participants to determine 1) if the way signaling pathways in one species react to a given stimulus really predicts similar response in another species, 2) which biological pathway functions and gene expression profiles are most parallel in rodents and humans, 3) how much that depends on the nature of the stimulus or data type collected, and 4) which computational methods are most effective for inferring responses between species.

Competitors will get access to about 5,000 human and rat samples Philip Morris generated for the challenge, and will look at 57 stressors to a single cell line exposed at different time points.

Browne suggests that the IMPROVER approaches for verifying results could be useful as well in the pharmaceutical, biotechnology, nutrition, and environmental safety industries. And Royyuru sees the project as a step toward creating “a verification methodology that will become routine industry practice.” Who knows how Philip Morris might utilize the outcomes? For better or worse, they may seek to create safer tobacco products.

-

(Reuters) - A federal appeals court on Friday upheld a ruling banning tobacco company Philip Morris USA, a unit of Altria Group Inc, from making false or deceptive statements about cigarettes.

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia upheld a 2009 injunction banning the company, which sells Marlboro and other cigarettes, from making misleading statements or implying health benefits.

The court had previously upheld injunctions placed under the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act, but the cigarette company brought a new challenge after Congress passed the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act in 2009.

Philip Morris said the newest act, which increased restrictions on the actions of cigarette companies, made the injunctions redundant.

But the company's history of non-compliance led the three-judge panel to agree with a lower court that there is no assumption Philip Morris will comply with the new law.

This is the thirteenth year of litigation between Philip Morris and U.S. government.

The case is United States of America et al. v. Philip Morris USA Inc. Number 11-5146.

-

Published in CSP Daily News

Published in CSP Daily News

NEW YORK -- Philip Morris International, the largest tobacco company in the world recently announced yet another stream of revenue growth. With more regulation threats being imposed on tobacco companies and smokers, Philip Morris is looking to explore alternatives, according to a contributed column on Seeking Alpha.

Governments globally have been attempting to regulate how and if cigarette companies can advertise. In addition, governments have hiked tax rates on cigarettes in an attempt to break people's addictions by robbing their wallets. Philip Morris has responded by beginning to seek revenue through electronic cigarettes, chewing tobacco and snuff.

Though Philip Morris' smokeless effort is minimal right now compared to the tobacco industry, the company does have revenue coming from their joint venture with Swedish Match AB in 2009. The smokeless products from this joint venture are currently being marketed and sold in Russia and Canada. Revenues are expected to grow significantly too, as this is only the beginning of their marketing campaign, the column states.

Philip Morris is also looking to follow in the footsteps of competitor British American Tobacco and begin marketing electronic cigarettes. Electronic cigarettes offer a somewhat healthier alternative to traditional cigarettes because when you smoke them, you inhale water vapor mixed with nicotine rather than harmful smoke. This is easier on your lungs, although the nicotine still has its normal effects. With consumers becoming more aware of the consequences of smoking, some have looked to electronic cigarettes as an alternative to help preserve their lung function.

Long-term Philip Morris believes that electronic cigarettes will expand its revenue opportunities worldwide, the writer states. Philip Morris has the highest EPS growth rate among the tobacco sector for the next fiscal year; it's estimated to be 11.2%, ahead of Lorillard, Altria Group and Reynolds American. Its revenue growth for next year is also expected to triumph in its sector by growing by a projected 5.51%. Philip Morris yields 3.3% at its current price.

-

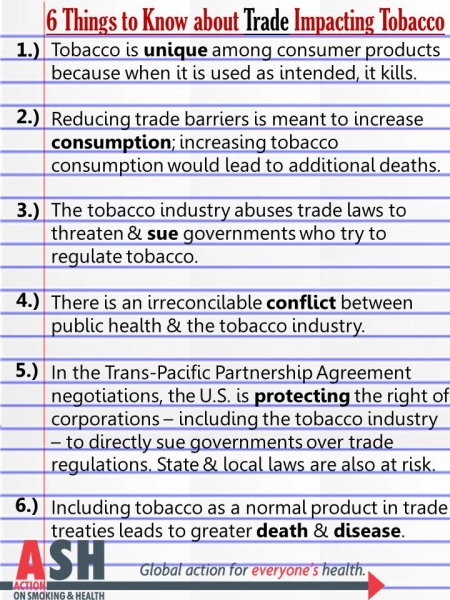

What does it mean to “carve out” tobacco from a trade agreement?

A “carve out” means an exclusion of tobacco products from the rules and benefits of the trade agreement. In effect, it gives complete protection for governments to regulate tobacco without fear of violating the trade agreement and being sued by the tobacco industry for doing so.

Current trade agreements require drastic change

Tobacco must be listed as an exception under all product references, removing its ability to benefit from free trade benefits between countries. This would not hurt any other products that benefit from the trade agreements because the exclusion would be product-specific.

The Tobacco Industry has sued many countries because of current international trade laws

Trade agreements allow the tobacco industry to drag governments before foreign trade tribunals and demand that anti-tobacco regulations be removed or weakened. Oftentimes, these cases are not about winning but are instead meant to impose the huge costs of litigation on governments, which governments must pay even if successful in their defense.

What is the irreconcilable conflict between the tobacco industry and public health?

Unlike other products that can become harmful when abused or overused, there is no “safe” use or amount of tobacco. The tobacco industry simply seeks to increase consumption of tobacco, while ASH and its public health allies seek a higher level of global health. There is no “happy medium” to be found between the tobacco industry and the public health community.

What is the Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement, and why does it matter?

The Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement (TPPA) is a free trade treaty currently being negotiated between the U.S. and eleven countries bordering the Pacific Ocean. It will become the largest regional trading bloc in the world once completed, ideally in 2013.

Negotiations for The Trans-Atlantic Trade and Investment Agreement (TTIP) between the U.S. and the European Union began in July 2013. It will be even bigger than the TPPA. In both negotiations, the U.S. is pushing for the right of corporations, including Big Tobacco, to directly sue governments in foreign trade tribunals. This ability to directly sue a government is a “chill” tactic used by Big Tobacco to discourage governments from implementing tobacco control regulations so as to avoid the cost of defending themselves in court against the tobacco industry, who can afford to drag out the cases for a long time. Learn more about the threat and opportunity of the TPPA>

Trans-Atlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP)

In July 2013, negotiation started for a free trade agreement that will be even bigger than TPPA, the Trans-Atlantic Trade and Investment Partnership between the U.S. and the 28 countries of the European Union. Several European countries have made great strides in fighting the tobacco epidemic, and may want to protect their laws from corporate lawsuits. Learn more about TTIP>

How many lives are at risk if tobacco continues to benefit from trade agreements?

The WHO estimates that 1 billion people will die from tobacco this century unless drastic actions are taken. One of those critical actions to take is carving tobacco products out of trade agreements. It is impossible to predict how many lives hang in the balance of the trade debate, but it is certainly millions worldwide.

-

Philip Morris International Inc. (PM), the largest publicly traded tobacco company, will spend as much as 500 million euros ($680 million) on a new factory in Italy as part of a drive to make products with lower health risks.

The plant, near Bologna, will start producing tobacco products that are heated with a special device rather than burned at the end of 2015 or early 2016, the New York-based company said in a statement today. The factory will have capacity to produce as many as 30 billion units a year, equivalent to about 6 percent of the European Union’s cigarette sales, the company said.

“This first factory investment is a milestone in our road map toward making these products available to adult smokers,” Chief Executive Officer Andre Calantzopoulos said in the statement.

Nicotine Race

In November, Philip Morris brought the launch date of the tobacco-heating product forward to 2015 from a previous forecast of 2016 or 2017. It will test it in a few cities in the second half of this year.

Unlike e-cigarettes, the company’s new product will contain tobacco to appease smokers’ cravings for the taste of a conventional cigarette.

The device looks like a hollowed-out fountain pen. The custom-built cigarette is inserted and the tobacco is heated to generate a smoking aerosol. The temperature is “significantly below” what’s generated by a traditional cigarette, PMI has said.

PMI has spent more than a decade trying to develop lower-risk products and started eight clinical trials on them last year, the company said.

Philip Morris already has a filter factory and a pilot plant in Bologna. The new facility will employ about 600 people. The company will also enter the e-cigarette market in the second half of this year.

www.bloomberg.com

-

-

FRONTLINE tells the inside story of how two small-town Mississippi lawyers declared war on Big Tobacco and skillfully pursued a daring new litigation strategy that ultimately brought the industry to the negotiating table. For forty years tobacco companies had won every lawsuit brought against them and never paid out a dime. In 1997 that all changed. The industry agreed to a historic deal to pay $368 billion in health-related damages, tear down billboards and retire Joe Camel.

FRONTLINE tells the inside story of how two small-town Mississippi lawyers declared war on Big Tobacco and skillfully pursued a daring new litigation strategy that ultimately brought the industry to the negotiating table. For forty years tobacco companies had won every lawsuit brought against them and never paid out a dime. In 1997 that all changed. The industry agreed to a historic deal to pay $368 billion in health-related damages, tear down billboards and retire Joe Camel.

This report recounts how it all started when Mississippi's Attorney General Mike Moore joined forces with his "Ole Miss" classmate attorney Dick Scruggs and sued tobacco companies on behalf of the state's taxpayers to recoup money spent on health care for smokers. Scruggs and Moore criss-crossed the country in a private jet hawking their battle strategy to other state attorneys general and eventually built an army of forty states.

Moore and Scruggs had a number of secret weapons. They took charge of explosive tobacco industry internal documents that no one else would touch. And they protected two of the most important whistleblowers in the history of the tobacco wars: Jeffrey Wigand, the first high-level tobacco executive to turn against the companies; and Merrell Williams, a paralegal who secretly copied thousands of internal documents.

And these Missippippi "boys" held another trump card. They offered a deal to Bennett LeBow, CEO of Liggett & Myers: break ranks with the industry and cooperate with the state attorneys general in return for financial stability. FRONTLINE tells how they also managed to get a back channel to President Clinton and Senate Majority Leader Trent Lott through political advisor Dick Morris.

But Scrugg's and Moore's success was not limited to getting the industry to a national settlement. FRONTLINE details for the first time how their efforts triggered a massive criminal investigation of Big Tobacco that threatens to put some in jail for deceiving the American public.

Partly because of this criminal investigation, strong forces in the public health community opposed settlement talks. FRONTLINE interviews Minnesota State Attorney General Hubert Humphrey III and former FDA Chairman David Kessler who balk at any "deal with the devil."

As of May 1998, the Senate is poised to pass broad anti-smoking legislation which would cost the industry over $500 billion. The tobacco firms have denounced this new deal claiming it will bankrupt them. But Congress -- once a servant of the industry in large part because of tobacco's massive political clout and contributions -- has now turned against it.

-

In 1998, the Attorney General's Office reached a settlement with the major tobacco manufacturers that imposes major restrictions on the industry's advertising and marketing machine, curtails its ability to fight anti-tobacco legislation in our political arena, and provides states quick mechanisms to enforce the agreement.

In 1998, the Attorney General's Office reached a settlement with the major tobacco manufacturers that imposes major restrictions on the industry's advertising and marketing machine, curtails its ability to fight anti-tobacco legislation in our political arena, and provides states quick mechanisms to enforce the agreement.

In addition, it provides states approximately $206 billion through the year 2025 - including $4.5 billion for Washington State - to help rectify the harm caused by tobacco. The tobacco settlement is the largest financial recovery in legal history.

The Master Settlement Agreement

The 1998 Tobacco Master Settlement Agreement (MSA) between tobacco companies and 46 U.S. states was the largest civil litigation settlement in U.S.history. Its central purpose was to reduce smoking, and particularly youth smoking in the U.S.

In the Agreement:

-

Each of the 46 states gave up their legal claims that the tobacco companies had been violating state antitrust and consumer protection laws.

-

The tobacco companies agreed to pay the states billions of dollars in yearly installments to compensate them for taxpayer money that was spent on patients and family members with tobacco-related diseases.

It Settled Lawsuits:

-

The MSA resolved litigation brought by over 46 states in the mid-1990s against majorU.S.cigarette manufacturers: Philip Morris, R.J. Reynolds, Brown & Williamson, and Lorillard, plus the industry's trade associations and PR firms.

-

It settled the state lawsuits that were trying to recover billions of dollars in costs associated with treating smoking-related illnesses.

-

The Attorneys General of the 46 states signed the MSA with the four largestU.S.tobacco companies in 1998.

It Created New Restrictions:

-

New limits were created for the advertising, marketing and promotion of cigarettes.

-

It prohibited tobacco advertising that targets people younger than 18.

-

Cartoons in cigarette advertising were eliminated.

-

Outdoor, billboard and public transit advertising of cigarettes were eliminated.

-

Cigarette brand names could no longer be used on merchandise.

-

Many tobacco company internal documents were made available to the public.

It funded anti-tobacco education:

- The MSA called for the creation of a nonprofit organization, the Legacy Foundation, funded by the settling states. This foundation was charged with educating the nation about the social costs, addictive nature and negative health effects associated with tobacco consumptio

- In 2001, the Legacy Foundation launched “truth” campaign. The American Journal of Public Health publishes peer-reviewed research that finds that the Truth campaign, funded by the MSA, is linked conclusively to 22 percent of the overall decline in youth smoking rates in 2000–2002—translating to 300,000 fewer smokers in 2002.

Since the MSA was signed in November 1998, about 40 other tobacco companies have signed onto the MSA and are also bound by its terms.

Under the agreement, state attorneys general are responsible for enforcing the restrictions on cigarette marketing and advertising.

-

-

1950

American scientists Ernst L. Wyndner and Evarts A. Graham publish a report that 96.5 percent of lung-cancer patients are moderate to heavy smoker.

1952

Liggett publicizes a study by Arthur D. Little showing that smoking Chesterfields has no adverse effect on the throat.

1953

A landmark study by Ernst Wyndner shows that painting cigarette tar on the backs of mice creates tumors.

1954

Eva Cooper sues R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Co. for the death of her husband from lung cancer. Cooper loses the case.

1954

The Tobacco Industry Research Committee (later becomes Council on Tobacco Research) issues a "Frank Statement" to the public. It's a nationwide two-page ad that states cigarette makers don't believe their products are injurious to a person's health.

1963

Brown & Williamson general counsel Addison Yeaman notes in a memo, "Nicotine is addictive. We are, then, in the business of selling nicotine, an addictive drug."

1964

U.S. Surgeon General Luther Terry issues the first surgeon general report citing health risks associated with smoking.

1965

U.S. Congress passes the Federal Cigarette Labeling and Advertising Act, requiring a surgeon general's warning on cigarette packs.

1971

All broadcast advertising for cigarettes is banned.

1972

Philip Morris's Marlboro becomes the best-selling brand in the world.

1982

U.S. Surgeon General C. Everett Koop finds that secondhand smoke may cause lung cancer.

1983

Rose Cipollone, a smoker, sues the tobacco industry. She dies in 1984 and her family takes up the lawsuit.

1985

Melvin Belli, who in Louisiana in 1958 had argued the first tobacco liability case to reach a jury, filed a claim of $100 million on behalf of Mark Galbraith, a three-pack-a-day smoker who had died at sixty-nine, against R.J. Reynolds in Santa Barbara, CA. It was the first such action to go before a jury in fifteen years, but Belli lost, holding that neither causation nor addiction had been proven.

1986

In May, Nathan Horton, a fifty-year-old African American smoker, files suit in Holmes County, Miss., for $17 million in damages from American Tobacco, on the use of fertilizers and pesticides in growing tobacco products in excess of government approved limits. His attorney, Don Barrett, brings the suit before a jury in January 1988, but the judge declares a mistrial because of a hung jury.

1988

Michael Moore is elected Attorney General of Mississippi.

1988

Merrell Williams is hired by Wyatt, Tarrant and Combs in Louisville to analyze and sort Brown & Williamson internal documents.

1988

Jackie Thompson first gets sick from tobacco related illness.

1988

Judge Lee Sarokin rules that he has found evidence of tobacco industry conspiracy in the Cipollone case; Liggett is ordered to pay Cipollone $400,000 in compensatory damages.

1989

Jeffrey Wigand starts work for Brown & Williamson as Vice President of Scientific Research.

1990

Don Barrett, the Mississippi attorney representing smoker Nathan Horton, wins the case against the industry during a new trial in Oxford, Miss. His client is awarded no damages in the case.Smoking is banned on U.S. passenger flights of less than six hours' duration.

1992

The U.S. Supreme Court rules that the 1965 warning labels on cigarette packs does not shield companies from lawsuits.

1992

Wayne McLaren, who modeled as the "Marlboro Man," dies of lung cancer.

1992

Merrell Williams is laid off from law firm of Brown & Williamson.

1992

Matthew Fishbein and other US Attorneys from the Eastern District of New York open a federal probe into criminal wrongdoing by the tobacco industry, focusing on Judge Sarokin's opinion in the Haines case. Sarokin called the industry the "king of concealment."

March 1993

See Below

May 1993

Mike Lewis visits Jackie Thompson in the Memphis hospital and begins discussing a suit against the tobacco industry on her behalf. In the elevator after the visit, Mike Lewis comes up with the idea of suing the tobacco industry on behalf of the state to recover costs from treating smokers.

Sept 1993

Jeffrey Wigand is sued for libel by Brown & Williamson for saying malicious things about the company president to another employee - they threatened suspended pay and health insurance.In the summer of 1993, the law firm Wyatt, Tarrant & Combs filed a civil suit accusing Merrell Williams of copying and removing confidential Brown & Williamson documents from the firm. The suit was filed after his lawyer had returned a box of these documents to the law firm. In a letter that accompanied the box, Williams' attorney alleged that Williams had suffered smoking related illnesses, a condition made worse by seeing the information in the documents, and he sought a settlement of Williams' claims.

Nov 1993

Jeffrey Wigand and Brown & Williamson sign a confidentiality agreement.

Feb 1994

FDA Commissioner David Kessler announces plans to consider regulation of tobacco as a drug, stating that tobacco manufacturers use nicotine to satisfy addiction.

2/28/94

ABC's "Day One" airs a report by producer Walt Bogdanich which claims that cigarette companies "spike" levels of nicotine.

Mar 1994

A national class action suit is filed on behalf of smokers, known as the Castano suit, after Peter Castano, a former Louisiana attorney who died of lung cancer.

3/7/94

Second "Day One" Segment airs, listing secret additives in cigarettes.

3/24/94

Philip Morris announces lawsuit against ABC in the circuit court for the city of Richmond, VA.

3/25/94

FDA Commissioner Dr. David Kessler testifies about tobacco and nicotine in Congressional hearings.

4/14/94

Seven leading tobacco company executives testify during Waxman's Congressional hearings that they believe "Nicotine is not addictive."

May 1994

Richard Scruggs hand carries Brown & Williamson internal documents to Waxman in Washington.

5/7/94

New York Times publishes Brown & Williamson internal documents, saying they were received by a government official.

5/12/94

Stan Glantz receives Brown & Williamson documents from "Mr. Butts."

5/18/94

Jeffrey Wigand (using the code name "Research") pays his first visit to Dr. Kessler's office at the FDA.

5/23/94

Mississippi Attorney General Michael Moore announces the filing of a lawsuit against the tobacco industry seeking to recoup the $940 million the state spent treating sick smokers.

June 1994

Geoffrey Bible is named President and CEO of Philip Morris

6/21/94

Dr. David Kessler testifies in Congressional hearings about the investigation into whether tobacco and niotine should be regulated by the FDA.

July 1994

Justice Dept opens criminal investigation into possible perjury by top tobacco company executives in their testimony before the Congress during the Waxman hearings.

8/17/94

Minnesota Attorney General Hubert Humphrey III files a Medicaid suit against the tobacco industry.

9/20/94

Attorney General of West Virginia files a Medicaid suit against the tobacco industry.

12/94

Florida Legislature passes a law making it much easier to sue the tobacco industry for Medicaid costs. The tobacco industry fights the passage of the law, but looses.

12/14/94

Congressman Marty Meehan sends an 111-page prosecution memo to the Justice Department, requesting that Attorney General Janet Reno open a formal criminal investigation against the tobacco industry and several of their law firms and industry organizations.

2/14/95

Brown & Williamson sues UCSF and Stanton Glantz demanding return of internal industry documents.

2/21/95

Attorney General Bob Butterworth of Florida files a Medicaid suit against the tobacco companies.

7/1/95

Stanton Glantz posts the Brown & Williamson documents on the Internet.

8/16/95

ABC agrees to settle their lawsuit with a prime-time apology and $15 million to cover Philip Morris legal fees. Separate $200,000 settlement with RJR.

Oct 1995

Steven Goldstone is named CEO of RJR Nabisco Holdings Corp., after having served as President and General Counsel.

11/5/95

New York Times story appears on CBS pulling full Wigand story for fear of tortious interference lawsuit.

11/12/95

"60 Minutes" airs cut tobacco piece without the full Wigand Interview. Several days later the Westinghouse/CBS merger is approved by CBS shareholders.

11/21/95

Brown & Williamson lead lawyer, Gary Moresrow, announces that they are suing Wigand for theft, fraud and breach of contract. Judge in Kentucky issues restraining order on Wigand, stopping him from discussing confidential documents.

11/27/95

Kentucky judge clarifys restraining order, saying Wigand is bound by his confidentiality agreement not to testify in any case without first cooperating with the tobacco industry lawyers.

11/28/95

Mississippi judge rules that State Attorney's can question Wigand despite restraining order made by Judge in Kentucky.

11/29/95

Jeffrey Wigand is deposed in Pascagoula in state of Mississippi's Medicaid lawsuit against the Tobacco Industry.

Dec 1995

Wigand is also questioned by US Justice Dept officials (Grand Jury Testimony) in the criminal investigation of the Tobacco Industry.

12/19/95

Massachusetts files a Medicaid suit against the tobacco industry.

1/26/96

Wall Street Journal runs piece including excerpts of Wigand's leaked deposition and places entire deposition on the Internet.

2/4/96

CBS runs full Wigand Interview.

3/96

The Liggett Group settles with five states and 67 law firms suing the industry - the first such agreement in 40 years of litigation.

3/96

Steven Goldstone, RJR Nabisco CEO says the industry would consider settlement.

3/13/96

Louisiana files a Medicaid suit against the tobacco industry.

3/28/96

Texas files a Medicaid suit against the tobacco industry.

4/11/96

New Jersey announces that they will file a Medicaid suit against the tobacco indsutry. Actually file suit on 9/10/96.

5/96

Federal appeals court dismisses the Castano national class-action lawsuit. Lawyers in the Castano group begin filing class-action lawsuits in individual states.

5/1/96

Maryland files a Medicaid suit against the tobacco industry.

6/5/96

Washington files a Medicaid suit against the tobacco industry.

7/18/96

Connecticut files a Medicaid suit against the tobacco industry.

8/96

A Jacksonville, FL, jury awards $750,000 to Grady Carter, who had sued Brown & Williamson. One juror says the released Brown & Williamson documents had an effect on the decision. Philip Morris's stock loses $12 billion in value within an hour.

8/20/96

Kansas files a Medicaid suit against the tobacco industry.

8/21/96

Michigan files a Medicaid suit against the tobacco industry.

8/22/96

Oklahoma files a Medicaid suit against the tobacco industry.

8/23/96

President Clinton announces that the FDA will regulate Nicotine as a drug.

9/10/96

New Jersey files a Medicaid suit against the tobacco industry.

9/30/96

Utah files a Medicaid suit against the tobacco industry.

10/96

B.A.T. Industries CEO Martin Broughton says a settlement of tobacco lawsuits would be "common sense."

10/17/96

Alabama files a Medicaid suit against the tobacco industry.

11/12/96

Illinois files a Medicaid suit against the tobacco industry.

11/27/96

Iowa files a Medicaid suit against the tobacco industry.

12/96

RJR hires North Carolina lawyer Phil Carlton to lobby the White House and try to meet with Mississippi Attorney General Michael Moore.

1/27/97

New York files a Medicaid suit against the tobacco industry.

1/31/97

Hawaii files a Medicaid suit against the tobacco industry.

2/97

Phil Carlton meets with White House deputy counsel Bruce Lindsey.The tobacco industry argues in U.S. district court in Greensboro, NC, that the FDA does not have the power to regulate tobacco.

2/5/97

Wisconsin files a Medicaid suit against the tobacco industry.

2/19/97

Indiana files a Medicaid suit against the tobacco industry.

3/97

The Mississippi Supreme Court rules that the state's lawsuit can proceed to trial.Liggett CEO Bennett LeBow settles with more than 20 states, and agrees to release internal industry documents.

3/18/97

Joe Rice, an attorney in Ron Motley's law firm, meets for the first time in Charlotte, NC, with tobacco company attorneys to discuss a settlement of all lawsuits facing the industry, the first time a major tobacco company representative sits across the table from an antitobacco attorney, apart from litigation.

3/31/97

Mike Moore, Dick Scruggs, Matt Myers, and John Coale meet with Phil Carlton.

4/3/97

Phillip Morris CEO Geoffrey Bible, RJR Nabisco's CEO Steven Goldstone, and their attorneys meet in Crystal City, VA, with state attorneys general to discuss a national settlement.

4/14/97

Alaska files a Medicaid suit against the tobacco industry.

4/22/97

Pennsylvania files a Medicaid suit against the tobacco industry.

4/25/97

U.S. District Judge William Osteen in Greensboro, NC, rules that the FDA has the authority to regulate nicotine as a drug. The tobacco industry immediately appeals the ruling.

5/5/97

RJR wins a lawsuit in Jacksonville, FL, filed by a smoker who died and blamed the cigarette maker for not adequately warning her of the dangers of smoking.

5/5/97

Montana files a Medicaid suit against the tobacco industry.Arkansas files a Medicaid suit against the tobacco industry.

5/8/97

Ohio files a Medicaid suit against the tobacco industry.

5/9/97

South Carolina files a Medicaid suit against the tobacco industry.

5/10/97

Missouri files a Medicaid suit against the tobacco industry.

5/21/97

Nevada files a Medicaid suit against the tobacco industry.

5/27/97

New Mexico files a Medicaid suit against the tobacco industry.

5/28/97

Scruggs and Moore meet with the leaders of the Public Health community in Chicago to discuss the potential deal.

5/29/97

Vermont files a Medicaid suit against the tobacco industry.

6/4/97

New Hampshire files a Medicaid suit against the tobacco industry.

6/5/97

Colorado files a Medicaid suit against the tobacco industry.

6/10/97

Oregon files a Medicaid suit against the tobacco industry.

6/97

Idaho files a Medicaid suit against the tobacco industry.

6/12/97

California files a Medicaid suit against the tobacco industry.

6/16/97

Puerto Rico files a Medicaid suit against the tobacco industry.

6/18/97

Maine files a Medicaid suit against the tobacco industry.

6/18/97

Rhode Island files a Medicaid suit against the tobacco industry.

6/20/97

The tobacco companies and state attorneys general announce a landmark $368.5 billion settlement agreement.

July 1997

Congress includes a $50 billion tobacco-tax credit in a new tax bill. New taxes paid by smokers will save the industry billions of dollars by reducing the amount of money companies would owe according to the settlement.

7/15/97

The State of Mississippi settles its Medicaid case with the tobacco industry for $3.4 billion dollars.

8/25/97

Florida settles. Tobacco companies agree to pay $11.3 billion.

8/29/97

Georgia files a Medicaid suit against the tobacco industry.

9/11/97

Senate votes to repeal the $50 billion tax break for the tobacco industry that was slipped into the tax cut legislation just before it was passed in July.

9/17/97

Clinton announces his position on the upcoming tobacco legislation in Congress.

10/13/97

Tobacco companies settle first secondhand smoke class-action in the Florida Broin case brought by flight attendants.

10/17/97

Philadelphia Judge Clarence Newcomer throws out a massive Castano group suit, a national class-action lawsuit against the cigarette companies, weeks before they were set to go to trial.

12/4/97

Cong. Bliley subpoenaes documents from four tobacco companies that are part of the Minnesota Medicaid case. The documents are released to his office and to the public later that week.

12/10/97

Hearings in Congressional Judiciary Committee on Lawyers Fees in the national tobacco settlement.

1/7/98

Justice Department brings charges against the DNA Plant Technology Corporation for their cooperation in developing Y-1 Tobacco, with high levels of nicotine and illegally exporting seeds to Brazil.

1/15/98

Texas settles with the tobacco industry for a record $14.5 billion.

1/26/98

Minnesota trial starts.

1/29/98

Tobacco executives testify before Congress that nicotine is addictive under current definitions of the word and smoking may cause cancer.

2/25/98

Tobacco executives tell Congress they would never agree to modify their advertising and marketing practices unless the lawmakers gave the industry substantial protection against lawsuits.

4/1/98

Sen. John McCain (R-AZ) passes the McCain bill in the Senate Commerce Committee. The bill gives the FDA unrestricted control over nicotine and is much tougher than the June 20th agreement. It provides no liability protection for the industry, just a cap on potential yearly damages.

4/8/98

Steven Goldstone of RJR Nabisco announces that RJR is pulling support for a settlement and complains that the McCain bill will bankrupt his company. Within hours, the rest of the tobacco industry backs away from the global settlement.

-

Steve Parrish is Senior Vice President, Corporate Affairs, of Philip Morris and representative for the tobacco industry in settlement negotiations. He is in favor of the national settlement and has argued that the tobacco industry will reform under the proposed regulatory framework contained in the deal. He was "at the table" during the settlement talks and was considered a rational and fair negotiator by the participants we interviewed. Previously, Parrish was General Counsel for Philip Morris and worked with Philip Morris International in Switzerland. Prior to joining Philip Morris, Parrish was a partner at the law firm of Shook, Hardy and Bacon in Kansas City, MS. He was the main tobacco industry attorney in the famous Cipollone case.

Steve Parrish is Senior Vice President, Corporate Affairs, of Philip Morris and representative for the tobacco industry in settlement negotiations. He is in favor of the national settlement and has argued that the tobacco industry will reform under the proposed regulatory framework contained in the deal. He was "at the table" during the settlement talks and was considered a rational and fair negotiator by the participants we interviewed. Previously, Parrish was General Counsel for Philip Morris and worked with Philip Morris International in Switzerland. Prior to joining Philip Morris, Parrish was a partner at the law firm of Shook, Hardy and Bacon in Kansas City, MS. He was the main tobacco industry attorney in the famous Cipollone case.

Q. Mr. Parrish, why did the industry try to settle litigation with the Attorney's General?

Parrish: Well, we had been thinking for some period of time about trying to come up with a way to resolve a number of the very contentious issues that were facing the industry. The Attorney's General lawsuits, the class actions, there was a lot of legislative and regulatory issues that were out there, and we were really trying to come to grips with was there a way that we could try to resolve as many of these issues as possible, and the Attorney's Generals cases were a part of that....because we just felt that we could continue the litigation, whether it was the class action cases, the Attorney General cases, and if we won the cases we would still be in litigation and we would still be fighting and we were really....analyzed the situation. We didn't want to keep fighting. We wanted to sit down with others, people that we had disagreed with quite strongly on a lot of issues and see if we could find some common ground and try to resolve some of the issues.

Q. To those of us on the outside it seemed like a great sea change. You're a veteran of that litigation; you come from Shook, Hardy and Bacon before you were at Phillip Morris.

Parrish: That's right, I was a trial lawyer before I came with Phillip-Morris.

Q. Representing the tobacco industry.

Parrish: I represented Phillip-Morris in a case in New Jersey back in 1988, that's right.

Q. So that tobacco industry was known, if you will, for never giving up, for spending any amount of money to defend itself. What caused the sea change? Was there an event, or do you remember a conversation?

Parrish: Well, I think it was really a lot of different things that came together at one point in time, which sort of led us to this almost historic opportunity we have. We had the individual cases, which we had always very successfully defended, we'd had a large measure of success defending the class actions lawsuits, we felt like we had a good chance to win the AG cases. We thought ultimately we would probably prevail in our FDA lawsuit. But it just seemed to us that even if we won, every one of those lawsuits, how would the situation be better? And we just felt like we owed it to our shareholders, to our employees and our business partners, retailers, wholesalers, and our consumers to see if there was a way to end the acrimony and try to find some common ground with the Attorneys General, people in the public health community, regulators and legislators.

Q. You don't remember...there wasn't a meeting or someone came in with a memo or a proposal or a draft and said, "Hey, we've got to change the way we're doing business."

Parrish: No, not at all. Actually, at Phillip Morris, for example, we had been talking about this issue for some time, and as it turned out the other companies had been doing the same thing. And I think in late 1996 there was a discussion among some of the CEOs about trying to sit down and see if we could fashion a way to work out some differences with some of those who had been our opponents in the past, find some common ground, and see if we could resolve some of the issues.

Q. Was there a fear that you might lose a lawsuit?

Parrish: Well, anytime you're involved in litigation you're always worried about whether you'll win or lose the case. But again, it was really more than just the being concerned about winning or losing an individual case, or a series of cases, because while the litigation was a very serious thing to us, there was more involved. It was very obvious to us that there was more involved. It was very obvious to us that people around the United States were very concerned about the issue of youth smoking. We talked to people, we did polling, and it was very obvious that people were concerned about that. We were concerned about it, so we thought "is there a way that we could address the 'youth smoking' issue?" The Attorneys General and others in their lawsuits had claimed that the youth smoking issue was central to their claims against the industry, and we thought that might provide an opportunity to address the youth smoking issue, as well some of the litigation issues.

Q. Well, Mike Moore and Dick Scruggs and others who participated in the negotiations say to us they asked you or...Mike Moore said they asked you or Phil Carlton....that they be serious when they come to the negotiating table. And they all say that they were stunned, initially, when the industry said, "we'll give up our first amendment rights" or advertising rights. Somebody must have had a discussion about giving up that, after all the litigation and all the money, and all the argument against doing that.

Parrish: Well, we certainly had talked about that before we sat down to begin the negotiations. And I think there were really two key events early on in the negotiations. One was when Jeff Bible, the Chairman of Phillip Morris, and Steve Goldstone, the Chairman of RJR and Nabisco, sat down with the Attorneys General, the class action lawyers and some people from the public health community, and indicated very firmly their good faith and the fact that they were willing to make fundamental changes in the way we do business, going forward. I think that was very sincerely communicated to those on the other side of the table and I think they were impressed by that. And then, very quickly, we moved to the issue of our advertising and marketing practices, and I think when we, early on, indicated a willingness to forgo things like the Marlboro Man and Joe Camel in our advertising to give up billboards all across the country, that they realized that we were there in good faith and we were serious and we really wanted to try to work something out.

Q. Before I go back into the history here, I'm confused: are the Marlboro Man and Joe Camel still out there, or are you guys taking them out of the market place?

Parrish: If the comprehensive resolution that we negotiated last June is enacted into law, then they will be gone.

Q. Because it's not a good idea?

Parrish: I'm sorry, I don't understand.

Q. Well, you're willing to take them out of your advertising campaign because it's been alleged that it attracts kids and young people...it's not a good idea to have that out there attracting young people.

Parrish: Well, if I understand your question correctly that is one of the differences of opinion, if you will, that we have had with others, to whether the Marlboro Man, for example, is what causes kids to smoke. We don't think it is, but we were willing to give up the Marlboro Man as part of a comprehensive resolution of all these issues that were facing us. So, certainly, if this comprehensive resolution is enacted into law you'll never see the Marlboro Man again in this country.

Q. But if it isn't?

Parrish: Well, if it isn't, then I think that all of the companies in the industry have indicated that they...while we will do everything we can to address the issue of youth smoking, that we are not going to give up our First Amendment rights to communicate with our adult consumers. And the Marlboro Man, for example, is one way to do that. We're perfectly willing to try to work to eliminate youth smoking and do everything we can...we can't do it all by ourselves, and that's why this comprehensive approach, which involves money for education campaigns for kids as well as restrictions on advertising practices of the industry, is a much better way to go in our view.

Q. Okay, let me go back to a little history. When the Medicaid suit was first filed in Mississippi, and I assume you monitor litigation (related to Phillip Morris and the industry), what was your reaction?

Parrish: Well, it was a new theory. It was something that we really hadn't seen in the courtroom before; there had been discussions about theories like that in the past, and any time you have a lawsuit filed against you you take it very seriously. This one in particular we took seriously for a couple of reasons: it was a new theory, and just because of the potential amount of damages that was being alleged in the case.

Q. So you weren't like many of the other people we've interviewed who said when they first heard about it they thought "ah, it's a new theory and it's never going to go anywhere."

Parrish: Well, we took it seriously. We did our legal research and thought that we would win the case, that the law, if you will, was on our side. But, again, anytime you have a major lawsuit filed against you, you have to take it seriously--you owe that to your shareholders.

Q. At one point the governor of Mississippi went into the Supreme Court of Mississippi to try to get the whole suit and his Attorney General out of court, and you and your colleagues joined him in that suit. Once you lost that suit, did you really take it seriously then?

Parrish: Well, that was certainly a set-back, but we were taking it seriously before then. We were preparing for trial and we were preparing for trial right up until the moment we settled the case. So we were disappointed with the court's ruling, but we were prepared for it, and we were prepared to go forward if that's what we needed to do.

Q. So they were going forward in Pascagoula, these country lawyers in the shopping center in Pascagoula, but you took them seriously. They weren't just a bunch of hillbillies out there.

Parrish: The lawyers in the state of Mississippi in that case are excellent trial lawyers. They have done very well for clients all over this country, and as I've come to know them through the negotiation process I have a tremendous amount of respect for their ability; they're excellent lawyers.

Q. Were you guys home cooked in Mississippi?

Parrish: Well, I don't know what you mean by "home cooked." The state of Mississippi has a court system which functions very well. I'm not sure I would say that we were "home cooked."

Q. You're in Chancery Court, no jury, in Pascagoula and I think that the beauty of this comprehensive resolution was that despite our differences of opinion, the AGs, the private class action lawyers and the representatives from the public health community all had certain things that we could find common ground on. I think the Attorneys General, for example, realized that bankruptcy of the tobacco industry is not going to solve the youth smoking issue. It's not going to solve the public health issues that are trying to be addressed in this comprehhe law. I don't think that we thought we were going to be treated unfairly by the judge or anybody. Any place you try a case there's going to be a local lawyer.

Q. Well, but in Mississippi there was another case where the plaintiff complained that your people came in and hired all the prominent citizens as jury consultants, put them in the audience, and he wound up losing the case. He felt he got reverse cooked, if you will. I was just wondering whether if because the Mississippi case, in a sense, you may have felt outmaneuvered.

Parrish: No, I don't think we felt outmaneuvered. I think we thought at the end of the day if we had chosen to litigate that case all the way through the appellate process we ultimately would have prevailed, but at the end of the day we would have decided that it was in the best interest of our company and our shareholders and the industry to try to resolve that case as part of a comprehensive resolution of all the issues. And our firm belief was that to litigate these cases, one at a time, year after year after year, was not really going to be a satisfactory outcome for anybody; not for us, not for the citizens of Mississippi or the other states, and that there had to be a better way than 50 AG cases around the country.

Q. Well, isn't there the threat that you may lose one, two, three of these multi-billion dollar judgments and have to go into bankruptcy?

Parrish: Sure, that would be a terrible thing, and it would be not only terrible from the industry standpoint and all the hundreds of thousands of people around the country who depend on the industry for their livelihood, but I would submit it would be a bad thing for the public, because if you have a jackpot justice system where one, two, or three states get all the money, then what happens to the rest of the states? They get nothing, and that's why the comprehensive resolution that we negotiated with the Attorneys General, the class action lawyers and others, is a much better approach because it insures that the claims of all individuals and states will be satisfying.

Q. Fear of bankruptcy would have been a logical motive, though, for you to settle.

Parrish: Well, certainly, if this industry were to be bankrupt that would be, as I said, would be a terrible thing.

Q. When your share...the stock you own in the company would be worthless.

Parrish: It would not be worth much. And I think we owed it to our shareholders to try to resolve not only the AG cases, but all these other issues as well, and I think that the beauty of this comprehensive resolution was that despite our differences of opinion, the AGs, the private class action lawyers and the representatives from the public health community all had certain things that we could find common ground on. I think the Attorneys General, for example, realized that bankruptcy of the tobacco industry is not going to solve the youth smoking issue. It's not going to solve the public health issues that are trying to be addressed in this comprehensive resolution, because there will just be new manufacturers, whether they're foreign-based manufacturers or new manufacturing entities here in this country. There could very well be a black market. And I don't think anybody wants that. So we all said we all have the same concern here, so how can we fashion a resolution that addresses the very legitimate interests of everybody around the table.

Q.You know, in interview after interview that we do, people continue to refer back to the Spring of 1994 when the CEOs all were sworn in and then said they didn't believe that nicotine was addictive. From hindsight now, how do you look at that hearing and the strategy of that hearing?

Parrish: I think, in hindsight, that hearing in April of 1994 in front of Congressman Waxman's Subcommittee, was one of the seminal events over the last number of years as it relates to tobacco, and it was a very important hearing.

Q. Was it a disaster for the industry?

Parrish: I don't know if I would say it was a disaster, but it certainly focused a lot of attention on the smoking issue in this country.

Q. Would you have done it differently today?

Parrish: I don't know with 20-20 hindsight whether I would have or not. Not that I was the one who was making those decisions but I just don't know.

Q. Maybe, could you clarify what the industry position is now between the 1994 testimony about nicotine addiction and risk factors related to health and recent testimony that there's some acknowledgment that you may have contributed to 100,000 deaths a year, and similar statements or confusing statements from my point of view.

Parrish: I don't think you can say there's an "industry" position on those issues. I think what you have is different companies have different positions. The CEOs of the different companies have different views, as a personal matter. And I think you've seen that reflected in the recent congressional testimony, so I don't think you can say there is a industry position on those issues.

Q. Do you believe that nicotine is addictive?